Researchers seek cause of massive B.C. rockslide that carved new canyon

A research team is flying up to the source of a massive landslide that ripped through a valley on B.C.'s Central coast in late November, in an attempt to pinpoint a cause.

They suspect glacial retreat played a role and say the devastating slide is a warning of how treacherous it can be to live below the unstable rock slopes that melting glaciers can leave behind.

Experts looking at satellite images believe a high-elevation rock avalanche hit a glacial lake and caused a violent 100-metre-high displacement wave or splash, releasing a violent outburst flood.

RELATED: Massive B.C. landslide imperils dwindling salmon stocks, says First Nations chief

The flood dislodged boulders and trees and sent a torrent of icy sludge into the sea below.

"It's pretty surprising. This is a large one," said Brian Menounos, professor of Earth Sciences and a Canada research chair on glacier change at the University of Northern British Columbia.

"The glacier has partially set this up," he said.

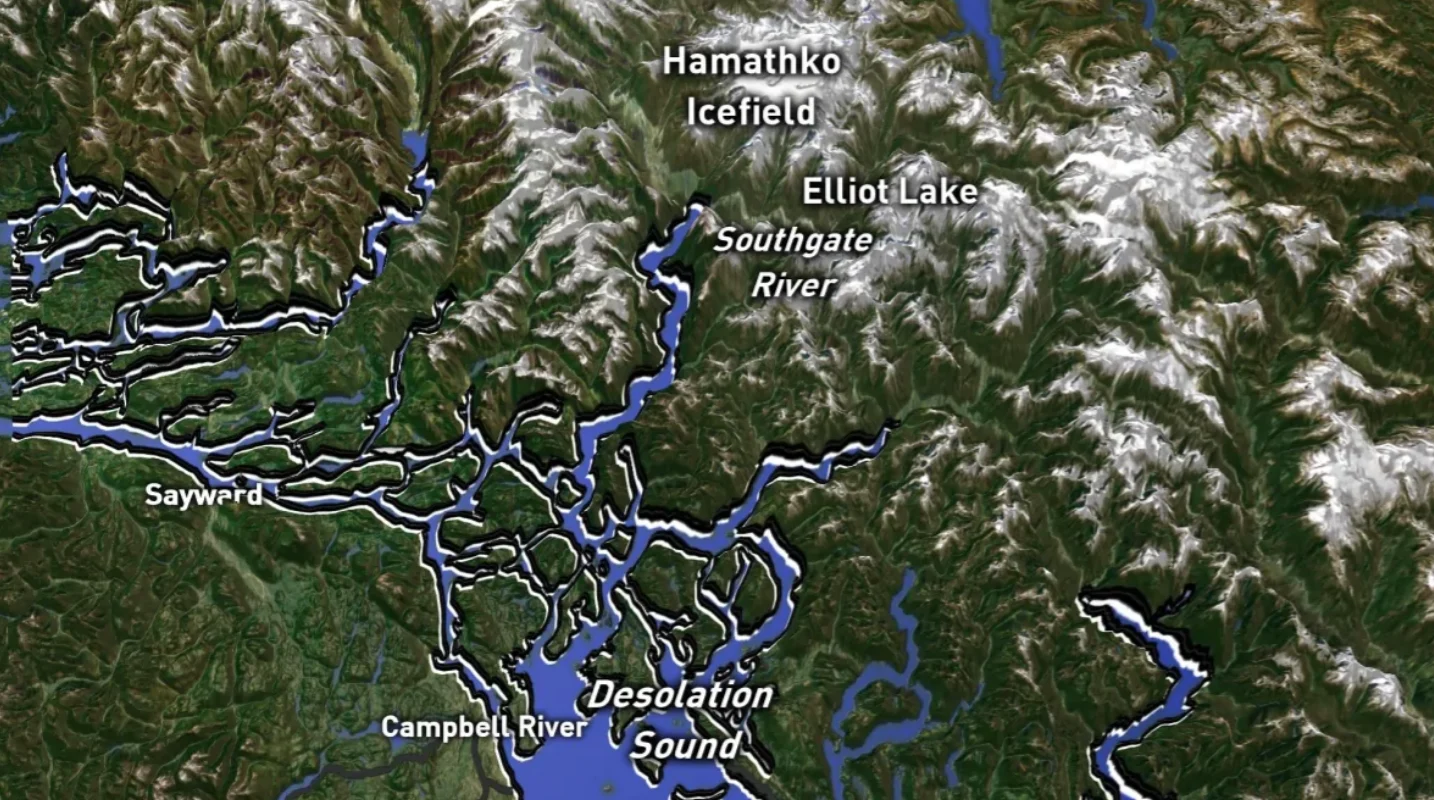

Image: Scientists suspect a massive landslide scoured the Elliot Creek bed, creating this canyon, after an initial outflow into a glacial lake triggered an 'outburst flood.' (Bastian Fleury/49 North Helicopters)

He said that retreating or melting glaciers often leave steep unstable slopes behind, but Menounos said the initial slide trigger — be it heavy rain, earthquake or another impetus— remains unclear.

"It showcases that our mountains are connected from the tops of the ice fields all the way down to the ocean," he said.

A photo taken from a helicopter shows the area where massive landslide is believed to have started in late November, 220 kilometres northwest of Vancouver. (Submitted by 49 North Helicopters via CBC News)

He's scrutinized Lidar (light detection and ranging) and satellite data on the topography of the slide area that is about 120 kilometres north of Powell River and 220 kilometres northwest of Vancouver.

That's where oceanographer Jennifer Jackson and a team of other researchers are flying by helicopter Thursday.

"This generated a tsunami where early indications show that [the initial splash] was 100 metres high. It flowed down into Bute Inlet, picking up lots of sediments and particles" said Jackson, of the Hakai Institute on Quadra Island, which conducts long-term research in remote parts of B.C.

Her team witnessed hundreds of logs floating in Bute Inlet on Dec. 2.

But nobody knew at that point how powerful the force was that had deposited this debris. Jackson said that the high-elevation slope that initially let go — had showed previous evidence of instability.

On Nov. 28, an estimated 7.7-million cubic metres of debris flowed oceanward, carried in a thick mud slurry the consistency of wet cement.

Jackson said the icy water actually lowered the temperature of the lower ocean currents in Bute Inlet by half a degree.

WAKE UP CALL

The cascade of events is already offering researchers an unprecedented amount of instant data that Jackson believes will teach much about how landslides affect the ocean.

She hopes it also informs people of the risks to populations that live in the shadow of unstable high terrain.

"We have all sorts of communities in British Columbia that this could have happened in. I'm hoping it's going to serve as a wake-up call that these are treacherous places as glaciers retreat. We are very lucky that there were no people living in this area at the time, because if there were any people living there, they would have died," said Jackson.

The debris flow obliterated millions of dollars worth of logging infrastructure about 10 kilometres below the initial event. The landslide — which nobody even noticed at first — created a seismic wave that was picked up on measuring devices all over North America, according to experts.

And it caused local shock waves over the loss of salmon habitat and forest.

Homalco First Nation Chief Darren Blaney said species including chum, coho and pink salmon, which were already dwindling, will be hurt by this event.

Andrew Horahan is vice president of western operations for Interfor Logging Operations. He sent a field geologist up to the source of the slide to survey the damage last week.

"It appears that we lost a significant amount of road construction, as well as a bridge and unfortunately a fair bit of developed timber," he said.

Scientists say the force of the event was equivalent to a magnitude 4.9 earthquake — and was about one-sixth the size of one of Canada's biggest landslides in 1965 near Hope B.C.

This article, written by Yvette Brend, was originally published for CBC News.