A lake that provides power to millions just fell to a historic low

Millions of people rely on hydroelectric power generated by the dam that creates Lake Powell. Years of drought are pushing the lake to dangerously low levels.

The water level at a lake that provides hydroelectric power to millions of homes and businesses is falling dangerously low—so low, in fact, that the dam may soon stop generating electricity. Officials are concerned that prolonged drought and increased stress on the Colorado River could push the pool elevation at Utah’s Lake Powell below this critical point.

LAKE POWELL GENERATES POWER FOR MILLIONS OF HOMES

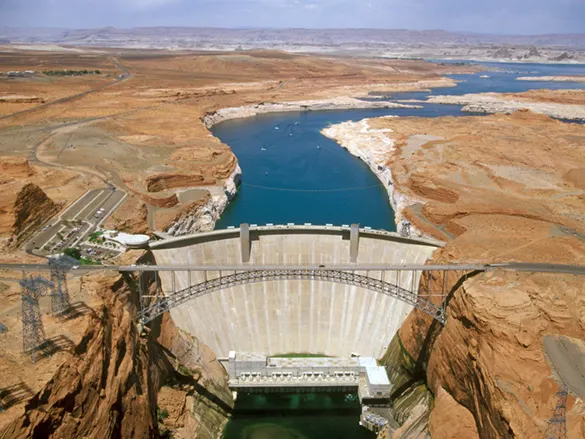

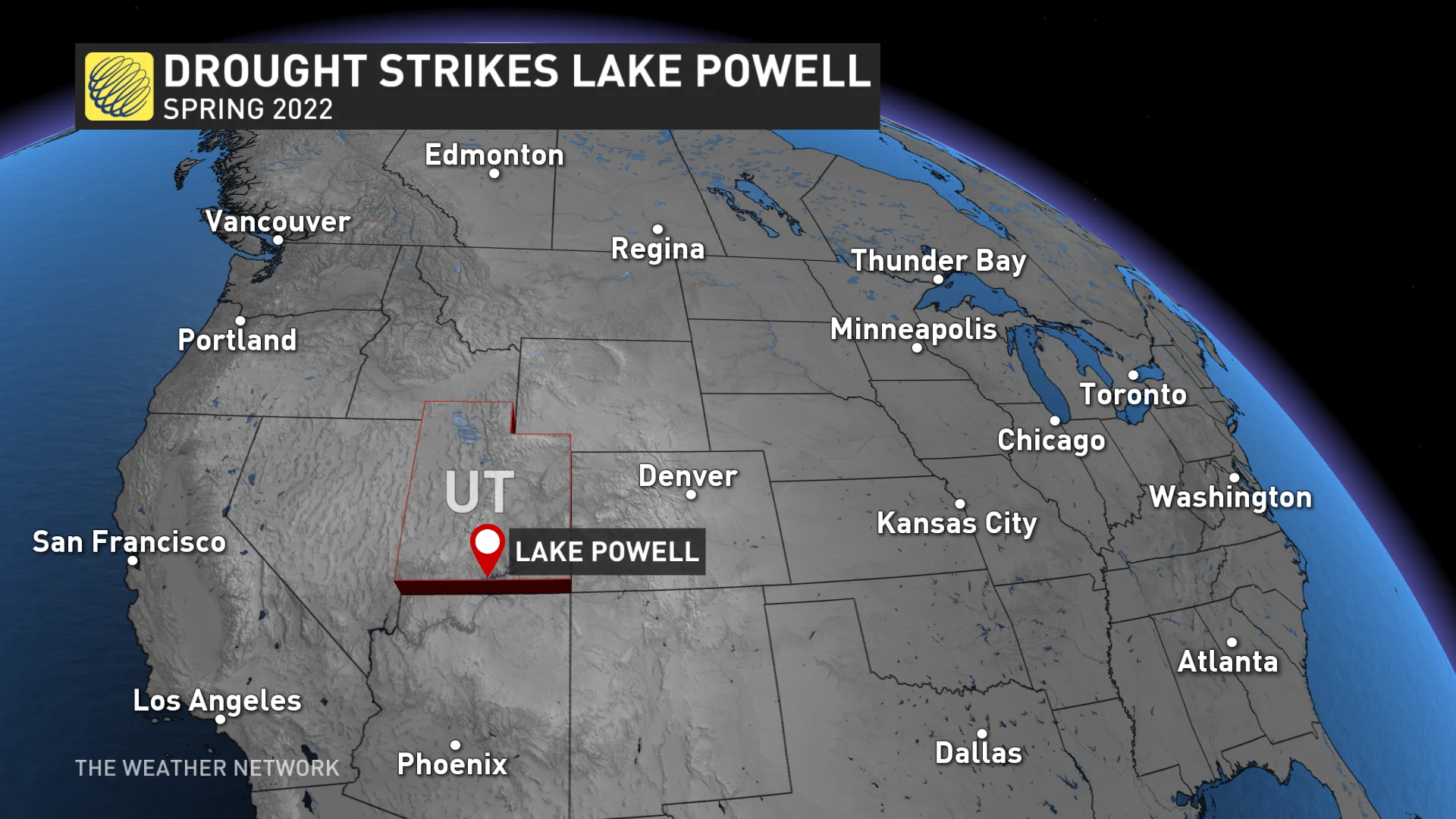

Lake Powell, nestled along the Colorado River in far southern Utah, is a vital resource for multiple states across the American Southwest. The U.S. federal government created Lake Powell by building Glen Canyon Dam, which began damming the Colorado River in 1963. It took another 17 years for the river to release enough water to fill the lake to capacity.

Hydroelectric power generated through the Glen Canyon Dam provides electricity to millions of customers across Arizona, Colorado, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

The lake, which is the second-largest human-made lake in the United States, also helps regulate water flow to ensure that all states are able to utilize their share of freshwater from the Colorado River.

YEARS OF DROUGHT TAKE A CRITICAL TOLL

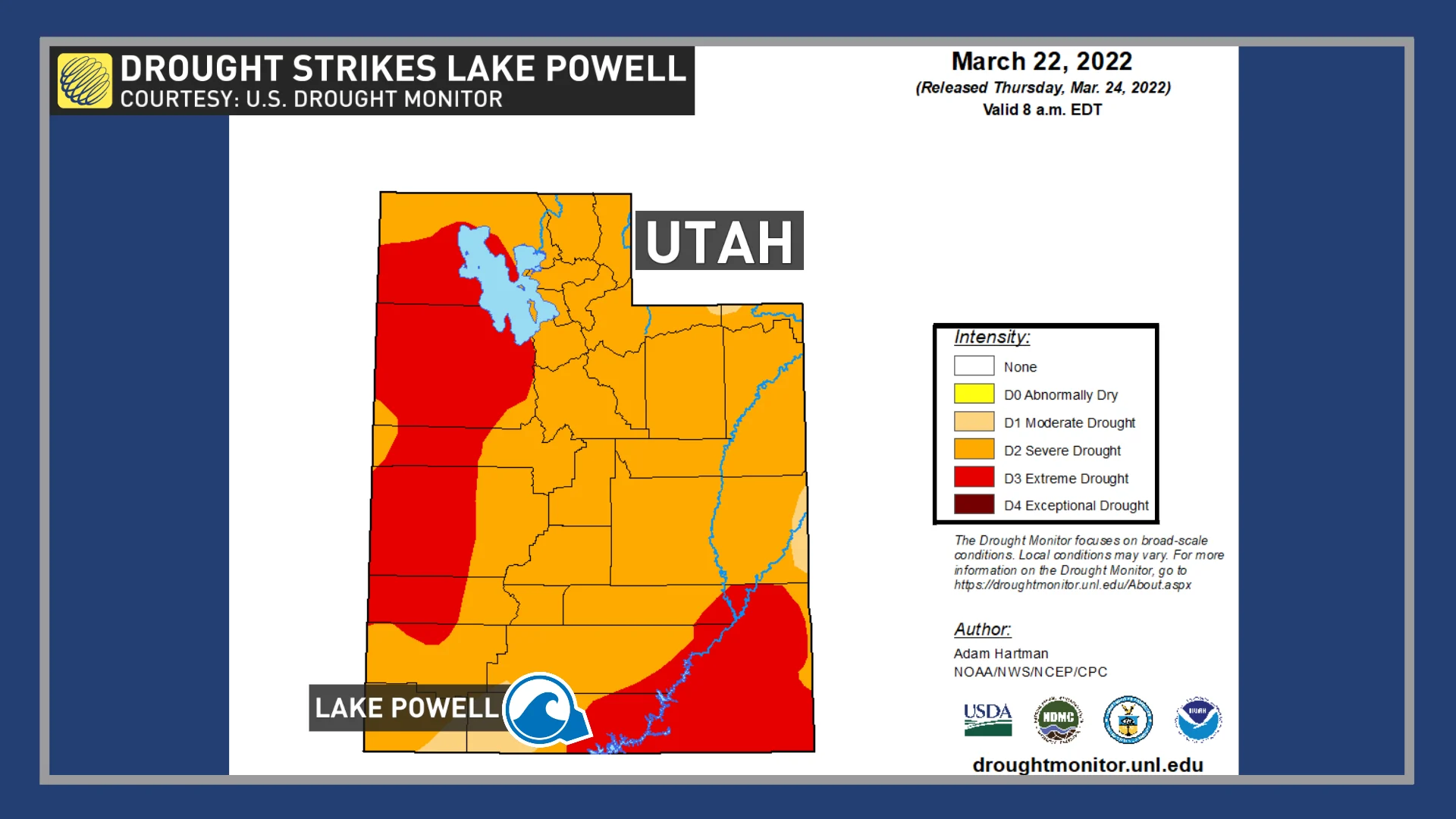

Years of high-impact droughts across the western United States have added stress to water resources throughout the region.

Southern Utah has been mired in persistent drought since August 2019, according to the United States Drought Monitor (USDM). Much of the region experienced an “exceptional drought,” the worst category on the USDM’s scale measuring the severity of dryness, for an entire year between late 2020 and late 2021.

As of March 22, Lake Powell and its surroundings were analyzed in an “extreme drought,” the second-worst category on the USDM scale.

LAKE’S ELEVATION CREEPING CLOSE TO ‘MINIMUM POWER POOL’

The United States Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) released a worrying status update on Lake Powell’s water level in the middle of March. The lake’s current water elevation of 3,525 ft (1,074 m) is creeping closer to the minimum power pool level of 3,490 ft (1,063 m), below which there’s not enough water to power the dam’s hydroelectric turbines to produce electricity.

The Associated Press reported in March that officials have never recorded a water level this low in Lake Powell’s existence.

If USBR’s projections indicate that Lake Powell’s water level could drop untenably low, the agency will consider releasing additional water from upstream dams in Colorado and Wyoming to make up for the deficit. The agency’s own projections indicate that it’s a distinct possibility, with about a 25 per cent chance of falling below the minimum power pool over the next couple of years.

Lake Powell at the Glen Canyon Dam (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation via Flickr)

Fortunately, the lake’s short-term prospects may be shored up by the impending snowmelt from nearby mountain ranges. The latest snowpack data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) show that the snow-water equivalent in the Upper Colorado Region is close to average for this time of year. Snowmelt is a significant source for freshwater replenishment in the west.

WATCH: U.S. COULD DECLARE FIRST-EVER WATER SHORTAGE

LONG-TERM EXTREME DROUGHT, POPULATION GROWTH THREATENS SHORTAGES

Several significant, long-term droughts in recent years have taken a toll on both Lake Powell and the Colorado River itself. The prospect of water shortages and water rationing is an ever-present topic of concern and debate across the western states.

Droughts and “megadroughts” will grow more common in places like the American west as we witness greater effects from climate change. “Hotter droughts and progressive loss of seasonal water storage in snow and ice will tend to reduce summer season stream flows in much of western North America,” the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said in its recent Sixth Assessment Report.

The increasing propensity for long-term droughts in the western United States is further complicated by the region’s rapid population growth.

Between 1980 and 2020, Utah’s population more than doubled, and Arizona’s population grew by more than 150 per cent. The dramatic increase in residents in recent decades has, in turn, substantially increased the demand for freshwater and electricity in a region where natural resources can barely keep pace.