How Montreal's forests are faring 25 years after the destructive ice storm

Éric Richard still remembers watching in horror as one of the largest natural disasters in Canadian history mangled almost everything he'd been striving for years to protect.

Working with a non-profit group dedicated to the conservation and preservation of Montreal's Mount Royal Park, Richard had a front row seat to the devastating impact the great ice storm of 1998 left on the mountain's forest.

"Some trees had just a few branches that were broken, some had their trunk breaking in two," he said. Others had slumped over due to the sheer weight of the thick ice that coated their branches.

In Mount Royal Park, more than 80 per cent of the trees — over 85,000 — were damaged to various degrees, with broken branches littering the forest floor and others, still attached, threatening to snap at any point.

SEE ALSO: The 1998 ice storm that called for the deployment of 16,000 military personnel

Following the historic ice storm in January 1998, trees were encased in thick coats of ice that bowed their trunks and snapped off branches. (Submitted by Les amis de la montagne)

The damage resulted in about 5,000 trees needing to be cut down.

"It was a serious threat to the forest," said Richard, scientific advisor to Les amis de la montagne.

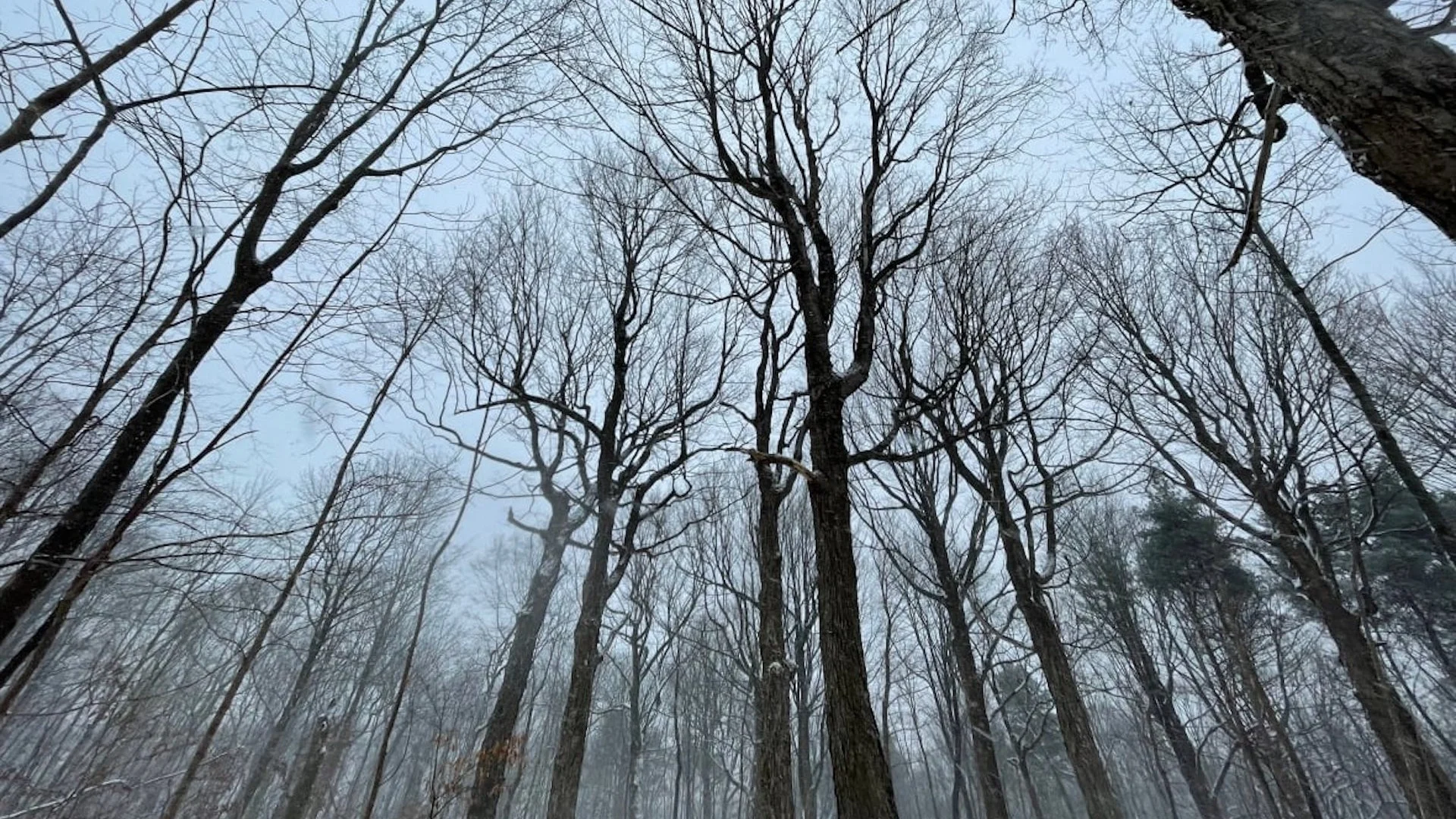

But a generation later, following the planting of more than 30,000 new trees and the surprising regenerative powers of old ones, Richard says you'd be hard-pressed to find clear evidence of the storm on woods that had suffered what seemed to be irreparable damage.

"The resilience of the forest is sometimes surprising us, how it can recover," he said. "If you look at the forest now, it's hard to find traces of the ice storm 25 years after."

Éric Richard, scientific advisor with Les amis de la montagne, says you'd be hard-pressed to find clear evidence of the historic storm on the park — save for the height difference between the old and the new trees. (Valeria Cori-Manocchio/CBC)

Storm changed ecosystem, landscape

While physical evidence of the ice storm, including bowed trunks and branch stubs, might mostly be behind us, that doesn't mean the storm hasn't shaped our urban forests or left an imprint on the landscape, according to Carly Ziter, a biology professor at Concordia University, who specializes in urban ecology.

"While we won't see the impact of the ice storm on individual trees, the ecosystem we have today is different than the one we would have, had we not had that large scale disturbance," she said.

For example, large trees that came down during the ice storm left equally large gaps in the park's canopy. This produced pockets of sunlight that, in turn, created conditions for invasive species of trees to spread and colonize the area.

Trees slumped over due to the sheer weight of the thick ice that coated their branches in January 1998. Benoît Côté, director of the Morgan Arboretum, believes wind gusts are a bigger concern than ice accumulation on our trees these days. (Submitted by Les amis de la montagne)

Native species, like the ash, also flourished in those gaps, but some 9,000 on the mountain have since been cut down after becoming infested by the tiny but destructive emerald ash borer — an invasive beetle that eats ash trees from the inside.

"So this insect [had] a bigger impact than the ice storm of 1998 on the forest of Mount Royal," said Richard.

The height of the forest was also altered by the storm, with trees planted in subsequent years standing about 10 metres tall now — about half the size of their neighbours.

Ziter says losing these large trees meant losing all the benefits that come with them, including off-setting urban heat and air pollution, as well as providing spaces for recreation and habitats for other animals and insects.

"So even though, on the one hand, nature and forests are incredibly resilient and they will regenerate and come back over time, it's not an easy or a fast process to replace nature when it has been lost," she said.

Importance of biodiversity

Experts say the current threats facing Montreal's forests include stronger and more frequent storms due to climate change, along with invasive insects like the emerald ash borer.

There are about 80 different species of trees on Mount Royal and more than 800 different species of plants and bushes that grow naturally in the forest. (Valeria Cori-Manocchio/CBC)

Benoît Côté, an associate professor at McGill University and the director of the Morgan Arboretum and Molson Nature Reserve, says with more extreme bouts of weather likely on the way, he worries more about the wind speed than ice accumulation.

"I think the storms are getting more violent … and as soon as you get to [wind gusts of] about 80 to 100 kilometres an hour, trees will go down," he said. "I'm not too sure what we can do to try to circumvent this problem in the future."

Ziter, for her part, says this emphasizes the importance of biodiversity. If urban forests are dominated by just a few species, which most are, including in Montreal, that makes them less resilient to disturbance in the future, she said.

"When we're planting new trees, there's much more of a focus on diversity, on planting not only different species, but trees with different functions, different shapes, different types of trees so that we can make sure that our urban forest is more resilient to these kinds of events in the future," she said.

A tree that's more resilient to an ice storm might not be the same one that's more resilient to a drought or an insect outbreak, Ziter said.

This part of the forest on Mount Royal, comprised of linden, white pine and nut trees, was planted in 2003 and overlooks Beaver Lake. The trees stand between 9 to 12 metres high, and will likely take another 25 years to reach the height of the rest of the forest's canopy, according to Richard. (Sabrina Jonas/CBC)

"There is no one perfect tree species that's going to withstand all of these stressors."

Richard says there are about 80 different species of trees on Mount Royal and more than 800 different species of plants and bushes that grow naturally in the forest.

Lessons learned

Despite the destruction caused by the 1998 storm, experts say this type of large scale disturbance gives us a chance to reflect and think about how we replant, rebuild and grow our urban forests in the future.

"We've learned a lot of lessons, I think, from the ice storm as well, in terms of not only the resiliency of our urban forest but in how we can manage our trees and our urban forests and recover from these kinds of events," said Ziter.

SEE ALSO: How the Rideau Canal skating season will survive in a warming world

She points to Quebec foresters, for example, who took what they thought was the best course of action at the time following the ice storm, but might have actually further traumatized trees.

Richard says the storm gave Montrealers an opportunity to learn more about how trees react to phenomena like this and about the fragility of the forest and how to improve its resilience.

"It was an occasion for all the professionals of the forest in Quebec to learn more about which species resist more or can succeed more, and it's changed the way they choose to plant trees in the streets," he said.

Zitar says, having seen how past events shape our contemporary ecosystems and the nature around us, Quebec must make fighting climate change a priority in order to protect our green spaces against future stressors.

"We need to get our emissions under control and combat climate change as the root cause of a lot of these disturbances," she said.

Thumbnail courtesy of Sabrina Jonas/CBC.

The story, written by Sabrina Jonas, was originally published for CBC News. It contains files from CBC's Valeria Cori-Manocchio.