Why that wild weather map you saw on social media is probably bogus

Big storms are a playground for bad information to spread like wildfire. Use caution when you stumble upon a weather map that doesn’t seem right—it’s probably not!

Beware of that outrageous weather map you saw on social media. The internet is awash with a goldmine of weather data that allows anyone anywhere to keep tabs on every aspect of our atmosphere. With all that information and all those colourful maps flying around, how do you know what to believe and what to avoid? The best rule is to trust what meteorologists are saying about a storm, and to take everything else with a grain of salt. Here’s why.

WEATHER MODELS DON'T TELL THE WHOLE STORY

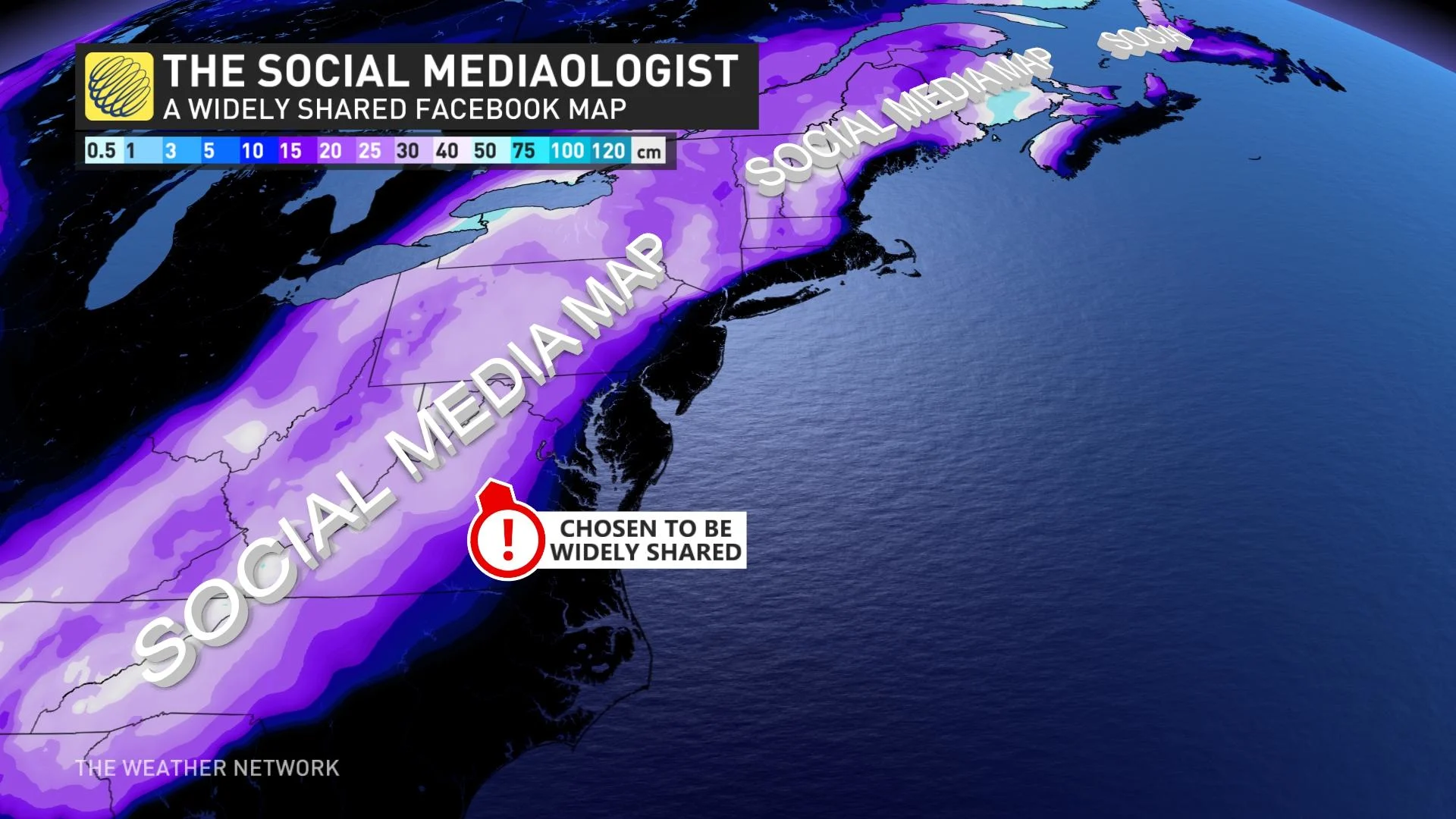

If you’re an active social media user, you’ve seen it before: the map with 2,000 retweets, the post from a local radio station that went viral, a dire warning from your friend’s nephew’s sister’s boyfriend. They always show oodles of snow on the way or a humongous hurricane swirling right for a major population centre.

That remarkable map probably came straight from a weather model, and that remarkable map is probably very wrong.

The breezy availability of raw weather model data, and the spread of those maps on social media, has turned out to be a huge problem when it comes to following accurate weather forecasts.

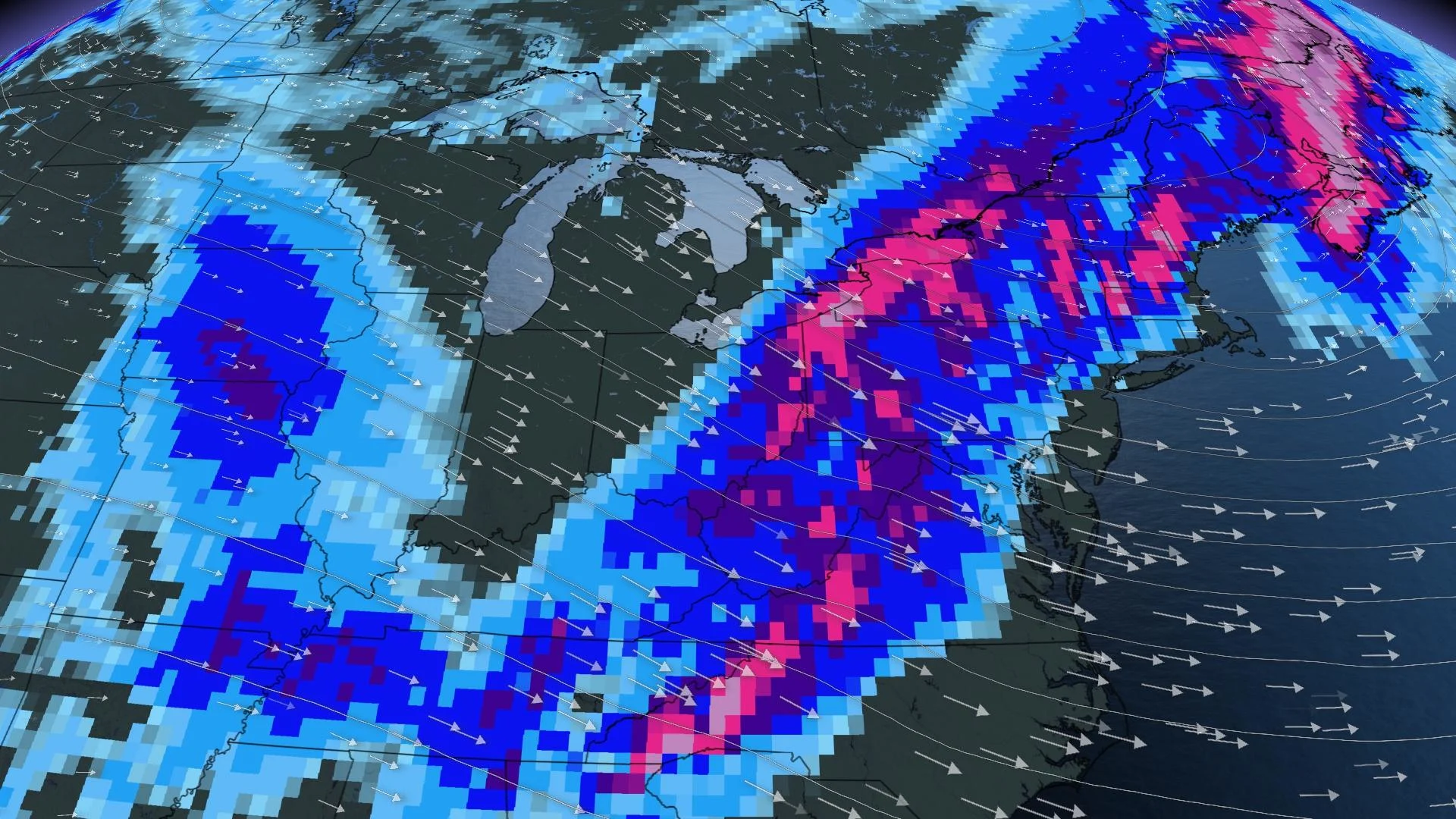

Weather models show a simulation of what might happen in the future. Scientists programmed these complex computer algorithms with an intricate understanding of our world—the atmosphere, the land, and bodies of water—and fed them past weather data so they have a solid foundation to accurately simulate what might happen over the next week or two.

The first problem is that what you see isn’t necessarily what you’ll get. In fact, what you see on a weather model hardly ever happens as shown.

Maps made by weather models are not forecasts. Meteorologists call weather models “computer guidance” for a reason. Forecasters use weather models alongside their deep knowledge and years of experience to craft their forecasts.

CONTEXT IS KEY

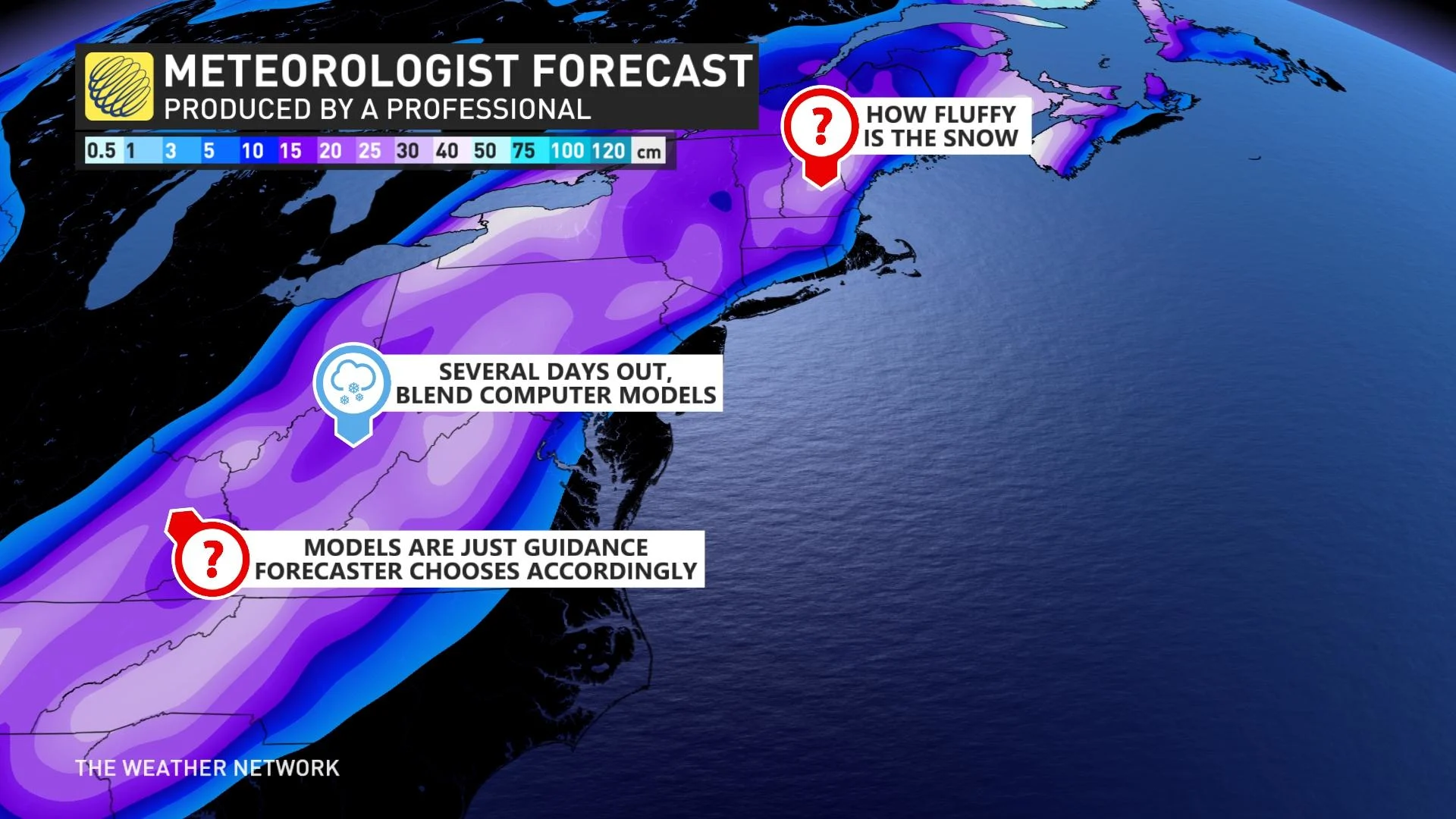

The two major global weather models meteorologists use most often are the GFS and the ECMWF models, often called the American and European models, respectively. There are plenty of other smaller-scale models, as well, including the North American Model (NAM) and the High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR).

The alphabet soup of weather models that meteorologists use every day each have their own strengths and weaknesses. Knowing the strengths and weaknesses of these models is a critical skill for developing a forecast.

We see weather models spill across social media all the time ahead of active weather. The two biggest events that attract this kind of out-of-context information are hurricanes and winter storms. The impactful nature of sprawling systems makes these high-stakes forecasts a must-read even for folks who don’t pay attention to the weather beyond checking the temperature.

Just looking at a hurricane simulation or a snow map from a weather model leaves out crucial context that you’ll only get from a human-created forecast.

SNOW OR NO?

Let’s use snow as an example.

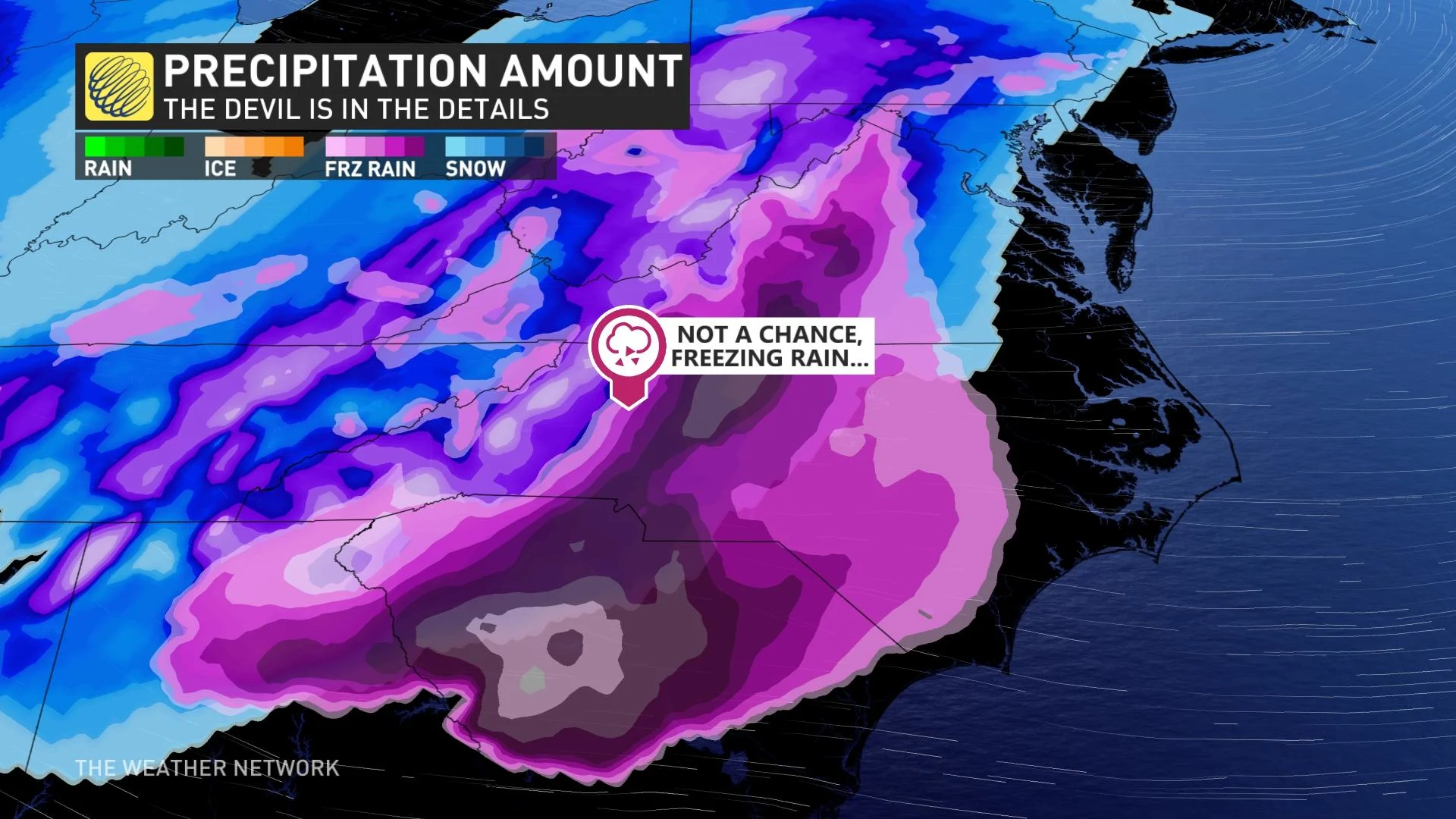

Certain models can sometimes get carried away with cold air, for instance, causing the model to show heavy snowfall and steep accumulations where rain, ice pellets, or freezing rain are actually more likely. Meteorologists account for these quirks when creating their forecast.

There’s also the rain-to-snow ratio. We all have experience with wet snow and dry snow. Wet snow is great for snowballs because it has a high water content. Dry snow is easy to sweep off the front porch because its low water content makes it powdery.

Most weather models default to a standard ratio of liquid precipitation to snowfall. The actual rain-to-snow ratio varies from one storm to the next, and even from one town to another. Predictions created by experienced forecasters factor in these varied liquid ratios and use those to adjust snowfall totals accordingly.

Timing is also a big factor. Weather models have improved in their accuracy over the years, allowing meteorologists to grow more confident in the potential for major winter storms many days before the first flake falls. Despite this increased confidence, there’s still too much uncertainty to pinpoint specific snowfall or ice totals four or five days ahead of the storm.

WATCH | WHY DOES YOUR LONG-RANGE FORECAST KEEP CHANGING? THIS GAME HAS ALL THE ANSWERS

MODELS DON’T EVEN AGREE WITH EACH OTHER SOMETIMES

Sometimes, the finer details get lost because the models can’t even agree on the path a storm will take. We often see this problem crop up across eastern Canada and the eastern U.S., where one model pulls a storm hundreds of kilometres to the west while another model shoves the storm an equal distance toward the east. These wide swings in a storm’s potential track have huge implications on whether you’ll see rain, snow, ice, or nothing at all.

This is also a problem during hurricane season. The path and intensity of tropical systems are dictated by large-scale and small-scale features in the atmosphere around the storm. The subtlest trough or ridge can push and pull on a system, sending it toward the coast or out to sea. Models rarely agree on these features.

Whether it’s a dicey snowstorm, a major hurricane, or anything in between, experience and knowledge can help a meteorologist figure out which outcome is favoured.

EASE OF ACCESS IS A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD

We live in the golden era of meteorological information. If you know where to look, you can find just about every satellite image, radar site, observation, map, and data point available to professional meteorologists, almost entirely free of charge.

This is a fantastic development for weather enthusiasts and students who want to learn more about the weather and develop a deeper appreciation for both the process of weather forecasting and the environment around us.

It’s also a burden for folks looking for accurate information and for forecasters trying to talk about what we do and don’t know about upcoming storms. These fantastical maps get so much traction that it’s difficult to elevate accurate and relevant information above the chaos.

When it comes to winter weather, hurricanes, or any type of active weather, trust the experts and use caution when you see something you can’t trace back to a reliable source.