Growing chill in the Arctic means a strengthening polar vortex

The polar vortex is beginning its annual strengthening. Here’s a dive into it and how this feature affects Canada’s winters.

The polar vortex is starting to strengthen as we tiptoe closer to the winter months.

Its very name can cast an icy chill over the most seasoned Canadian’s skin. The polar vortex is a mainstay of winter weather in the Northern Hemisphere, but it grew its fearsome legend during the brutal cold snap of 2014.

SEE ALSO: Canada's 2022 Fall Forecast: Is winter poised for an early arrival?

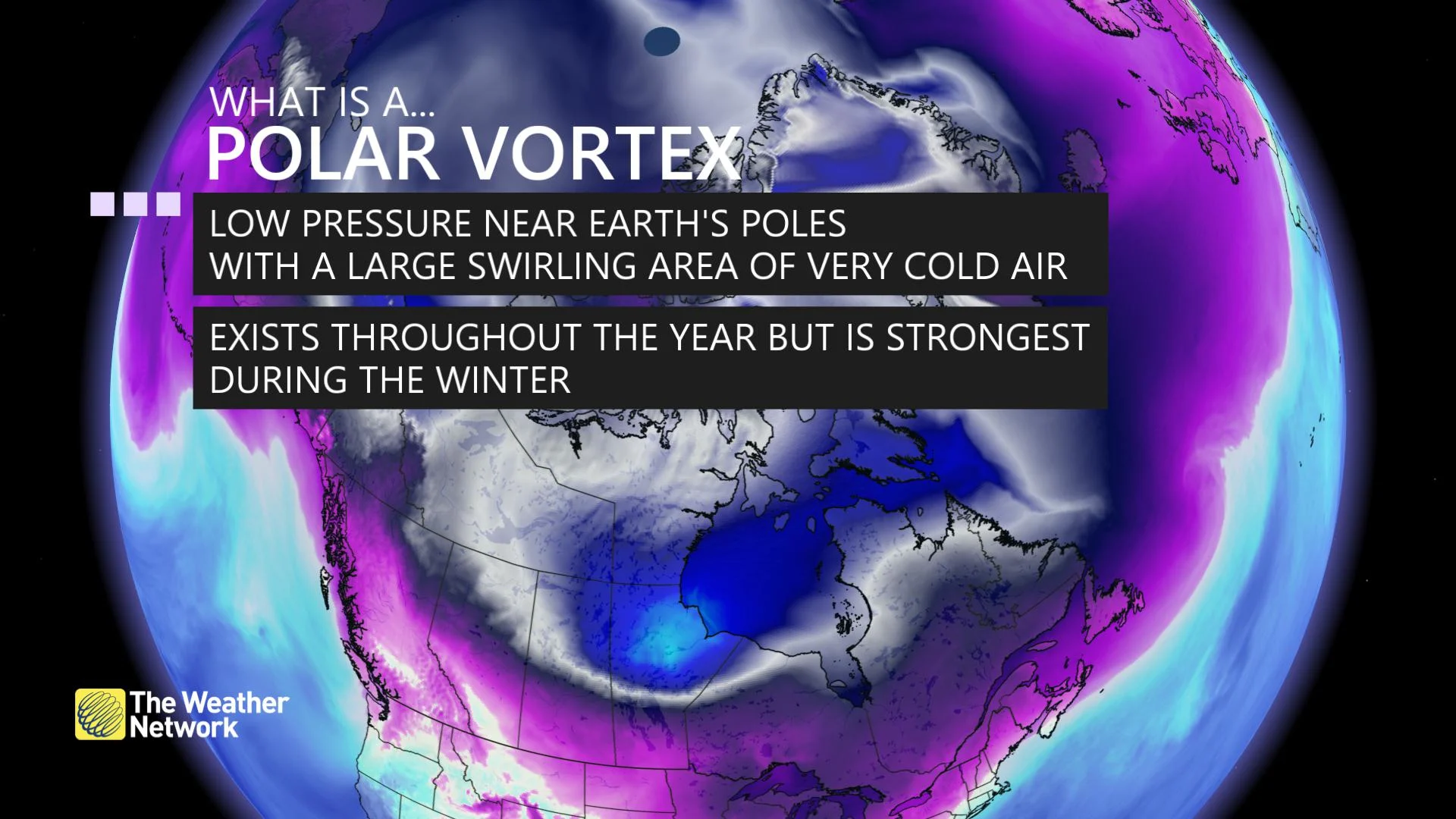

A polar vortex is a large-scale circulation that wraps around the Arctic Circle for the entire year. This circulation, which stretches from the surface all the way up to the stratosphere, can grow very strong in the winter and weakens tremendously during the summer months.

Now that the days are shrinking as the sun’s rays slip ever farther into the Southern Hemisphere, the polar vortex is starting its annual strengthening trend amid the growing chill in the Arctic.

DON'T MISS: What is La Niña? And how does it impact global weather?

This ever-present circulation is a critical factor in our fall and winter weather because it usually acts like a barrier that keeps winter’s coldest air confined to the far northern latitudes.

However, it doesn’t always work out like that. Major cold snaps across North America, Europe and Asia are often dictated by the whims of the polar vortex.

It seems like a paradox, but a stronger polar vortex is correlated with a milder winter for folks at lower latitudes, while a weaker polar vortex is bad news if you’re not a fan of cold weather.

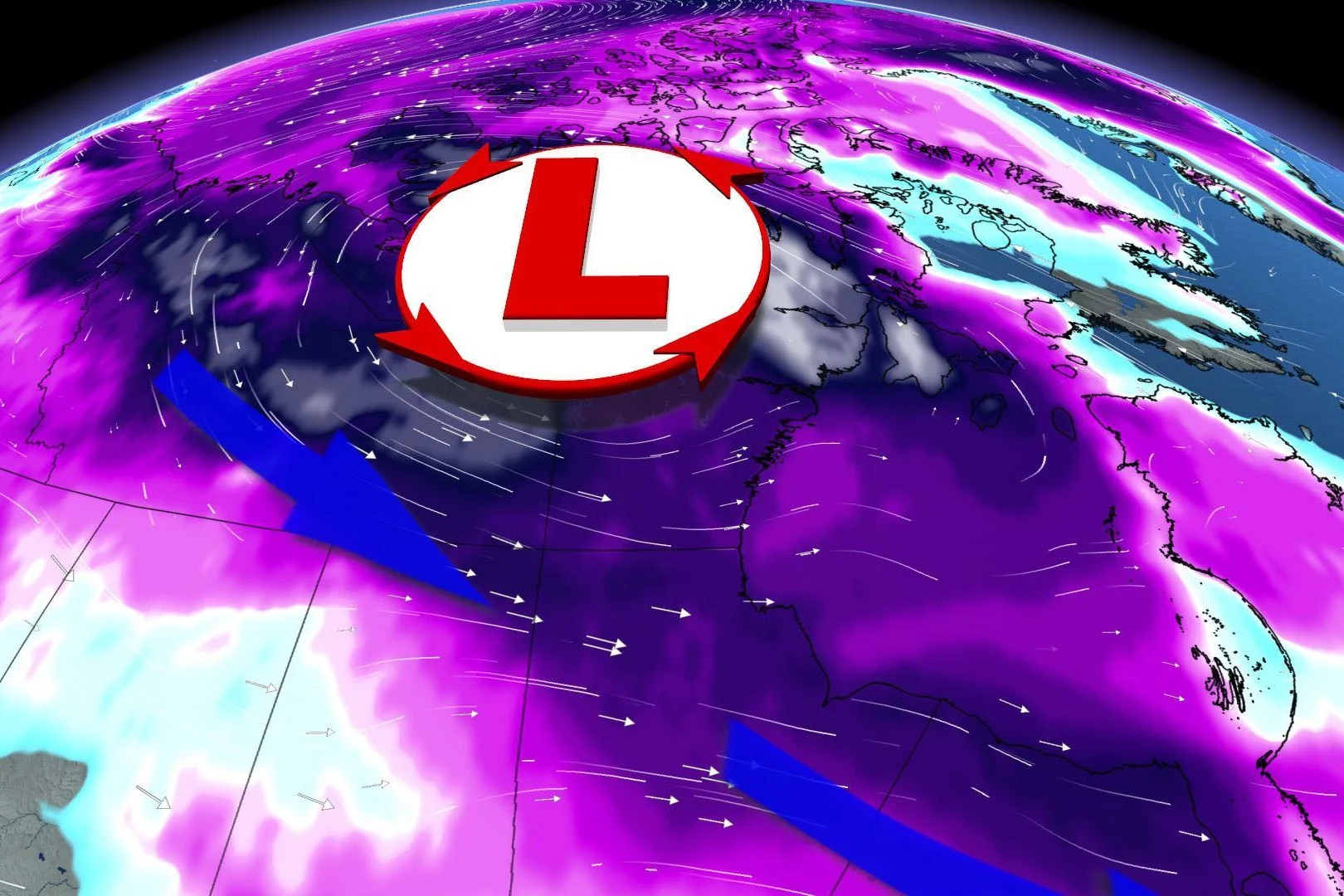

If there’s a significant disruption in this circulation, say for instance, a strong low-pressure system knocks it off balance -- the entire circulation itself can break down and become wavy.

These troughs, or lobes, of the polar vortex then swoop down to lower latitudes, allowing bitterly cold air to follow the trough and spill south.

Sometimes, a lobe of the circulation will break off completely and become a stubborn, upper-level cutoff low. These cutoff lows can stick around one region for days or even weeks at a time, making them responsible for some of the most brutal temperatures we can experience outside of the Arctic.