NASA pics show Venus' surface 'glowing like a piece of iron pulled from a forge'

The Parker Solar Probe captured the first direct views of the surface of Venus we've seen in 40 years!

The surface of Venus is shrouded in layers of cloud, but on a recent flyby, NASA's Parker Solar Probe actually spotted the surface glowing through those clouds.

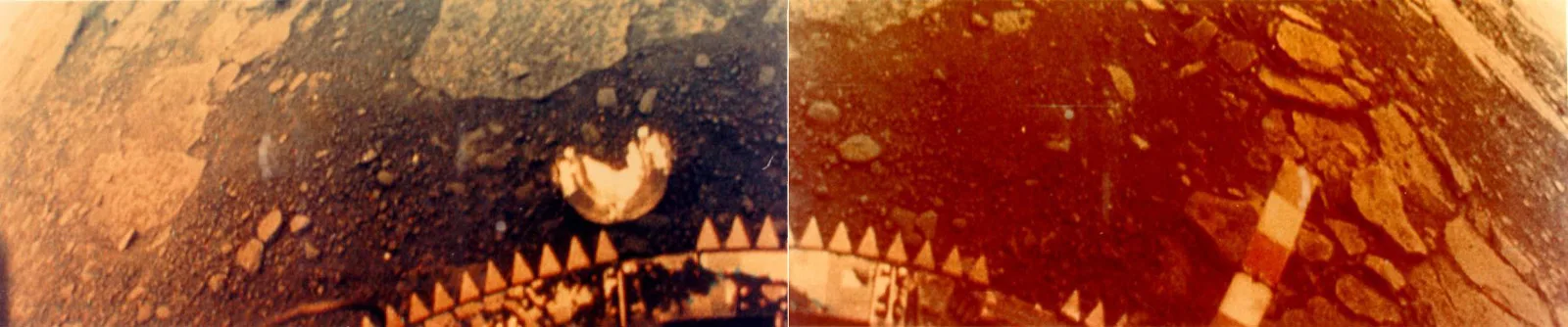

In 1975, the Soviet Venera 9 and 10 probes returned our first-ever pictures of the surface of Venus. These were followed by images from the Venera 13 and 14 probes in 1982. In the decades since, we've only seen views of the cloud tops, or very specialized radar or infrared images of the surface terrain.

Now, NASA's Parker Solar Probe has given us a new look, as its highly-sensitive WISPR cameras captured the surface glowing through the layers of cloud.

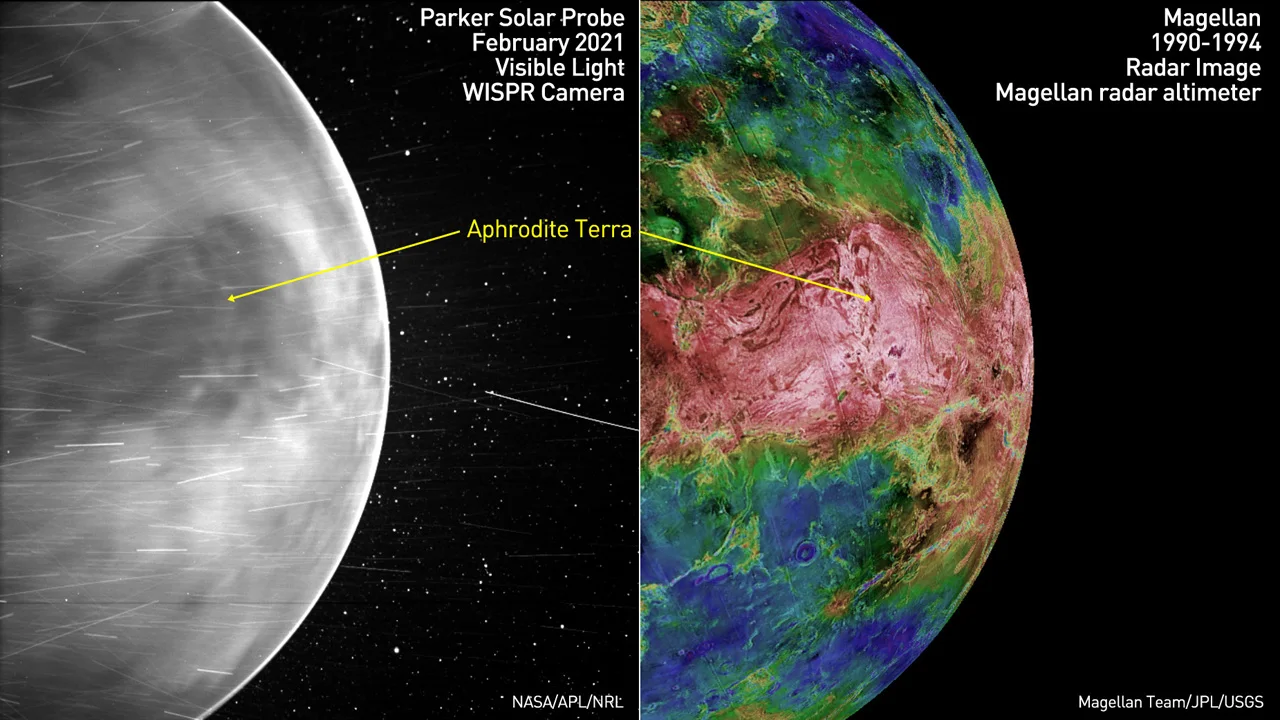

Taken in July 2020, during Parker Solar Probe's third flyby of Venus, this image shows the continent of Aphrodite Terra (dark, image centre) flanked by bright lowlands. Credit: NASA/APL/NRL

"The surface of Venus, even on the nightside, is about 860 degrees [Fahrenheit]," Naval Research Laboratory physicist Brian Wood said in a NASA press release. Wood is the lead author of a new study published this week that analyzed PSP's flyby images of Venus. For reference, 860°F is 475°C.

"It's so hot that the rocky surface of Venus is visibly glowing, like a piece of iron pulled from a forge," Wood said.

When the WISPR cameras on the spacecraft were designed, planetary imaging wasn't exactly on the team's mind. These cameras were specifically built to capture imagery of the Sun's corona and the solar wind. So, the first glimpse the cameras gave of the surface of Venus, above, was an unexpected bonus. The mission team was only hoping for a close-up look at the planet's cloud tops as the spacecraft sped by. Instead, they got much more.

This side-by-side comparison shows Parker Solar Probe's image of the nightside of Venus from July 2020 (left) with false-colour radar imagery from the Magellan spacecraft in the early 1990s (right). Aphrodite Terra, one of Venus' three immense continents, is clearly visible in the PSP view. Credits: NASA/APL/NRL/Magellan Team/JPL/USGS/Scott Sutherland

According to NASA: "Clouds obstruct most of the visible light coming from Venus' surface, but the very longest visible wavelengths, which border the near-infrared wavelengths, make it through. On the dayside, this red light gets lost amid the bright sunshine reflected off Venus' cloud tops, but in the darkness of night, the WISPR cameras were able to pick up this faint glow caused by the incredible heat emanating from the surface."

When PSP made its next Venus flyby, in February 2021, the team was ready, instructing the spacecraft to take multiple images as it zoomed past the planet.

Watch below: Venus' surface glows through its cloud layers on Parker Solar Probe's fourth flyby

"Venus is the third brightest thing in the sky, but until recently we have not had much information on what the surface looked like because our view of it is blocked by a thick atmosphere," Wood said. "Now, we finally are seeing the surface in visible wavelengths for the first time from space."

Parker Solar Probe's mission is to investigate the Sun and the solar wind. In the process of its mission, the spacecraft draws closer and closer to the Sun, and the method it uses for this is to fly past Venus for a little extra 'kick' from the planet's gravity. As of now, in February 2022, PSP has made five Venus flybys. It is due for at least two more before the expected end of the mission — one in August 2023 and another in November 2024. Further images captured by WISPR during those encounters could provide us with even more knowledge about Earth's sister planet.

These two views of the surface of Venus were taken on March 1, 1982 by cameras on the Soviet Venera 13 probe, during the 127 minutes that it was able to operate before succumbing to the harsh environment. Credit: NASA/NSSDCA/Courtesy of the USSR

NASA said that since different minerals glow in different wavelengths of light when heated, these WISPR images and those taken in the future could help scientists plot a more detailed map of the geology of Venus.

"We're thrilled with the science insights Parker Solar Probe has provided thus far," Nicola Fox, division director for the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters said in the press release. "Parker continues to outperform our expectations, and we are excited that these novel observations taken during our gravity assist maneuver can help advance Venus research in unexpected ways."