Six fascinating ways weather affects your daily flights

From contrails to plane-effect snow, weather plays a fascinating role in our everyday flights

Flying is a marvel of modern technology that we take for granted today. Dreams of soaring speckle human history—a feat that’s now so routine it’s a humdrum affair.

We may have figured out how to temporarily overcome gravity, but we’re still at the whims of mother nature when we take to the skies. Here’s a look at some of the fascinating ways weather plays into our daily flights.

DON’T MISS: Six annoying ways weather forces airlines to cancel your flight

Turbulence is frightening but (mostly) harmless

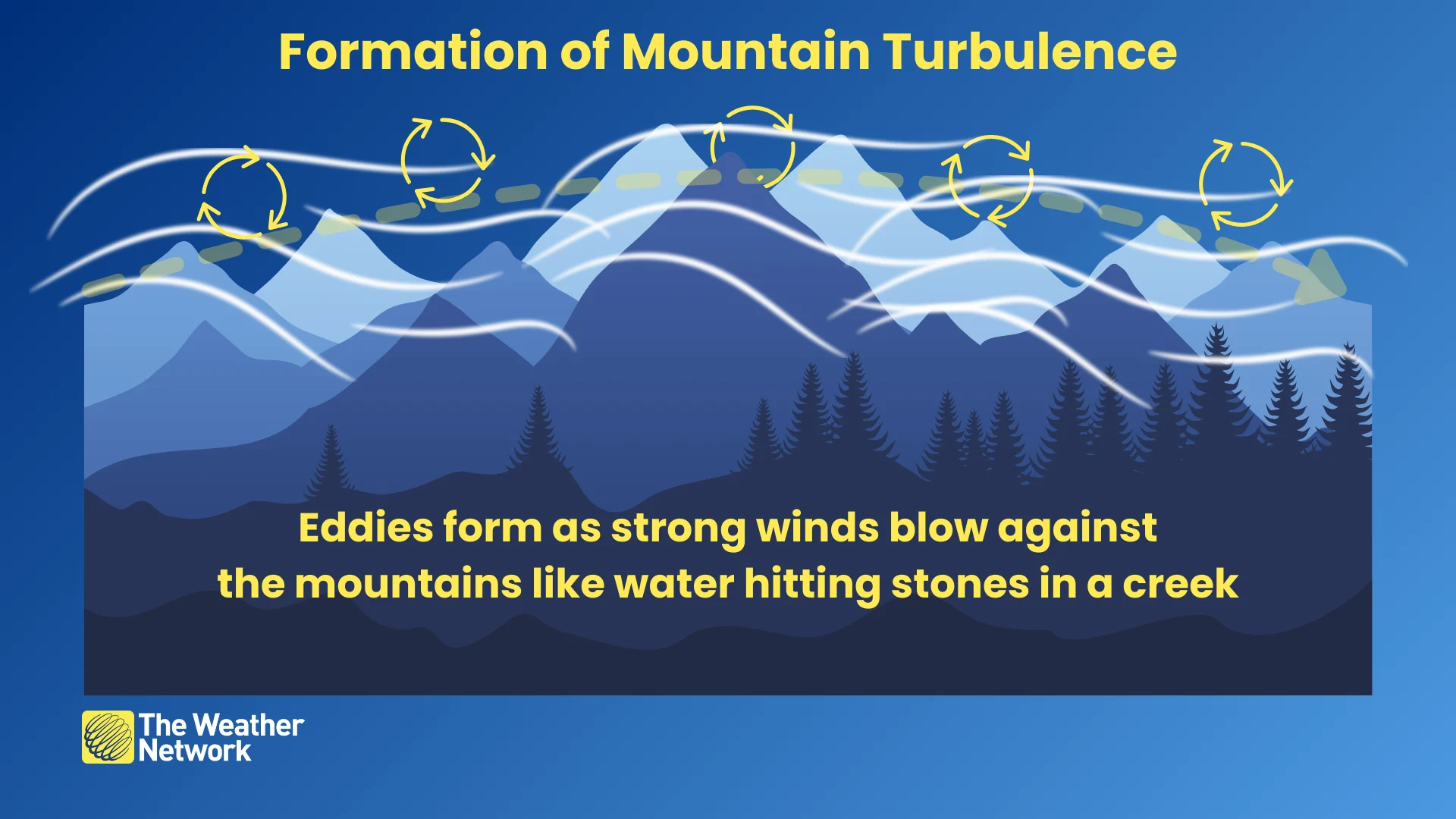

Turbulence is simply air in motion. Every little bump and jostle you feel during a flight is the result of features like wind shifts, rising or sinking air, or the eddies that form when winds blow over mountain ranges.

Airplanes are built to withstand a tremendous amount of stress from turbulence. While even the most severe turbulence you’re likely to encounter is harmless, it’s wise to buckle up to prevent injury from bumping around or things bumping into you during one of these uncomfortable experiences.

Delays are common due to visibility and ice

Travel delays and cancellations are an unavoidable fact of flying. Bad weather at home or along some leg of your journey can force airlines to make schedule changes to keep folks safe.

Poor visibility is one of the leading causes of flight delays. Modern passenger aircraft are capable of being flown via instrumentation from takeoff to landing. But most airlines have policies in place that require certain visibility thresholds on takeoff or landing in order to maintain safe operation.

Ice is another big factor behind scrubbed flights. Even a tiny film of ice is unacceptably risky because it roughens the airplane’s surface and hampers the lift needed to take flight. Freezing rain, freezing fog, or icing at certain altitudes are sometimes just too dangerous to chance.

Brilliant contrails follow behind high-flying planes

High-flying jet aircraft often leave behind dazzling displays of cirrus clouds in their wake.

These condensation trails, or contrails for short, are simply the result of hot, moist jet exhaust condensing when it comes in contact with frigid air at higher altitudes.

Depending on humidity, winds, and air temperatures, these contrails can disappear almost immediately or stick around for minutes or even hours. A day with high humidity aloft can even encourage these cirrus clouds to spread out into a thin, wispy blanket floating high against the blue sky.

Streamers flow off wingtips on humid days

Contrails aren’t the only clouds an airplane can produce. Planes leave behind quite the air current in their wake. One of these currents is known as a wingtip vortex, created by air streaming off the tip of each wing.

Swift swirling motion within each vortex creates a localized area of low pressure, which can cause the water vapour in the air to condense much like we’d see in a funnel cloud.

The end result is a tube of vapour trailing behind the tip of each wing. Wingtip vortices are most common on very humid days while a plane is taking off or landing.

Some flights can trigger rain or snow showers

We’ve all heard of lake-effect snow, and even nuclear-effect snow, but have you heard of plane-effect snow?

Under very special conditions, the hot exhaust of a jet engine can ‘kickstart’ the production of snowfall when an airplane flies through clouds with supercooled water droplets.

These water droplets, which remain liquid below the freezing point, can’t freeze into snowflakes until they have something to freeze onto. Fine particles in jet exhaust provide the nucleus for snowflake formation, creating localized snow showers near busy airports.

The change in air pressure even affects you personally

It’s not just the aircraft itself that feels the effects of the extreme environment of the upper atmosphere. Our bodies strain to acclimate to the sudden changes in air pressure that occur when we fly at high altitudes.

Airplanes are pressurized to the equivalent altitude of about 2,000 to 3,000 metres, which strikes the perfect balance between keeping passengers safe and maintaining acceptable pressure on the cabin itself.

Even at this pressurization, we’ve lost about one-quarter of the atmosphere’s weight pressing down on us while flying along at cruising altitude. This causes discomfort within our sinuses, including the dreaded need to pop our ears.

The reduced air pressure even affects the way we perceive taste. Lower air pressure—not to mention the extremely dry air on airplanes—reduces our ability to sharply discern between different flavour profiles. It’s a difference that can make food taste bland—possibly an unfair knock on airline food’s reputation.