Hurricane forecasts are better today than ever before—here’s how

The improvement in hurricane forecasts is one of the biggest and most noticeable leaps in technology over the past few decades

Today’s hurricane forecasts are a monumental achievement in public safety. Weather forecasts overall have improved tremendously over the past couple of decades, but the advance in hurricane predictions is remarkable.

Tropical systems often took a terrible toll in the old days. A hurricane that roared ashore in Galveston, Texas, on September 8, 1900, killed more than 6,000 people when its ferocious winds and storm surge overwhelmed the seaside community.

Check out The Weather Network’s hurricane hub for all the latest on tropical systems across the Atlantic and around the world

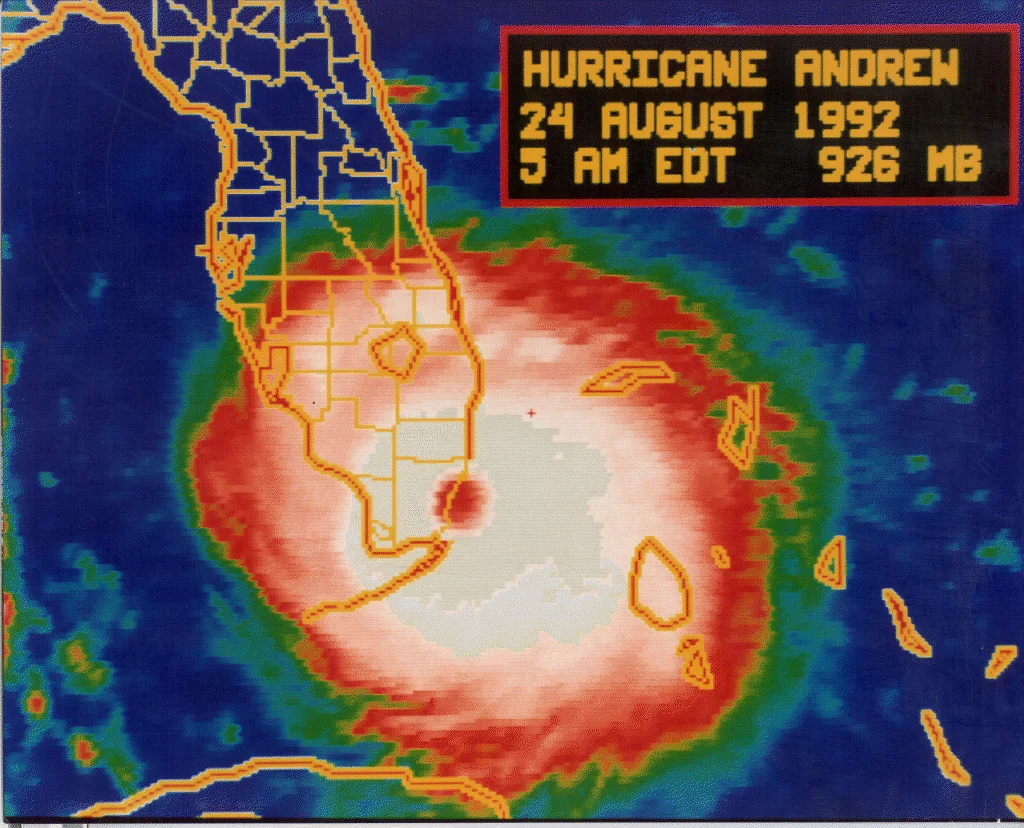

Hurricane Andrew at landfall in August 1992. (NOAA/NHC)

Just one or two generations separate a time when vast storms caught victims by surprise from the modern-day technology that allows us to track the birth of ferocious storms half a world away.

But unlike the arrival of smartphones or the advent of medical treatments, weather forecasts have quietly improved to the point that it’s easy to take them for granted—until we see how fast they’ve improved in such a tiny timeframe.

Track forecasts are impressive

There are two main components to a hurricane forecast: track and intensity.

Track forecasts have demonstrated the biggest improvement over the years. Today’s forecasters predict a storm’s track at 12- to 24-hour intervals out to five days in advance. Uncertainty and errors in the track forecast naturally grow with time.

Experts at the U.S. National Hurricane Center (NHC) review their forecasts and calculate their average track error at the end of each season. This error is how forecasters build the cone of uncertainty we see on weather maps.

Take a look at how these errors have improved over the past 50 years:

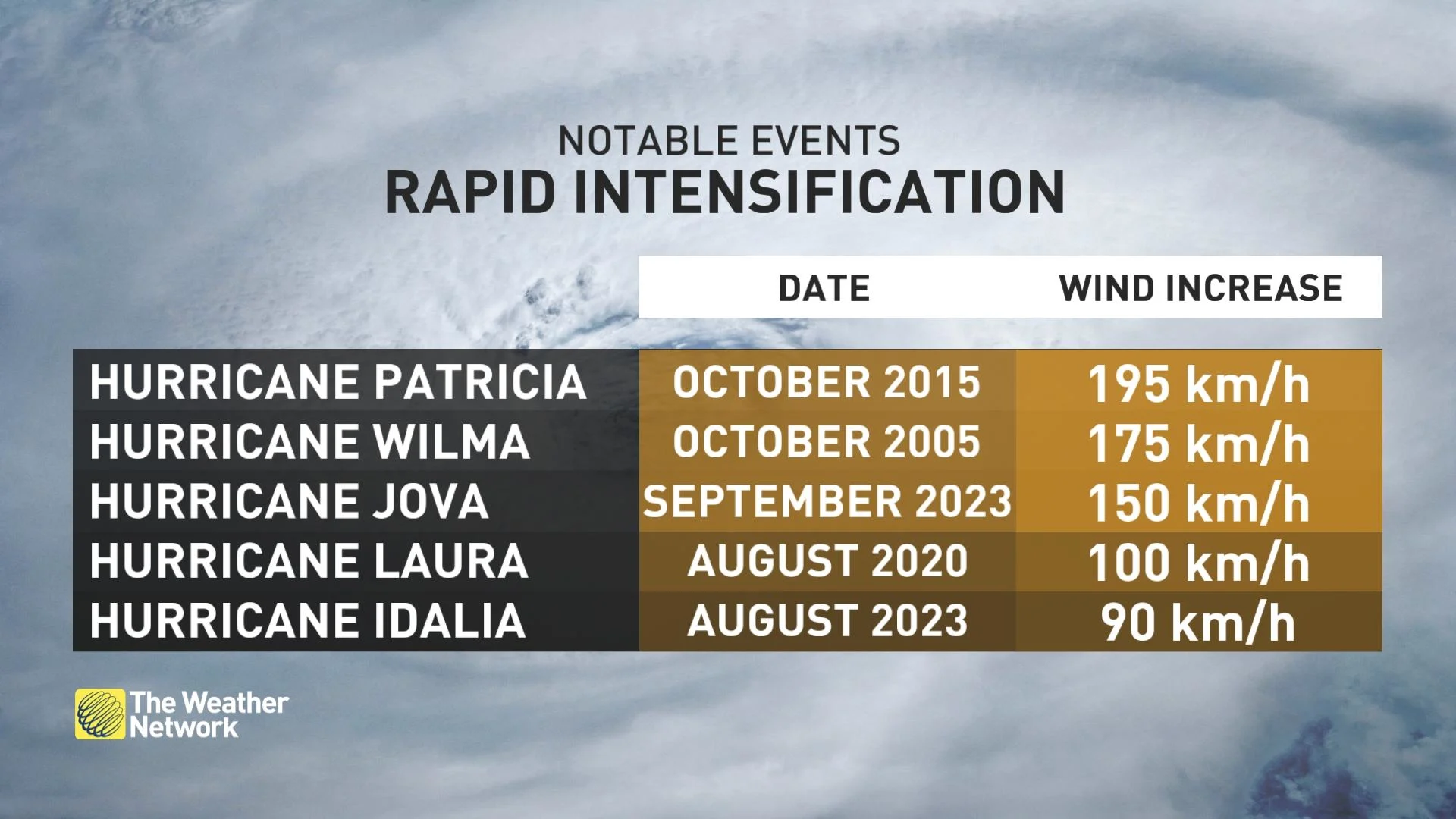

MUST SEE: It's not just your imagination, Atlantic storms are getting stronger faster

The average forecast back in 1973 had a huge error even just one day in advance. Forecasters were off by an average of 217 km at the 24-hour mark. Compare that to an average error of just 69 km at the same point today.

It’s even more impressive to see how much the average track error has improved two and three days in advance. A three-day forecast back in 1973 was off by about 672 km, which is nearly the same distance between Toronto and Chicago. 50 years later, the 2023 hurricane season saw a threefold improvement to just 213 km.

Consider that weather models were off by more than 450 km just three days before Hurricane Andrew slammed into southern Florida as a Category 5 in 1992. Forecasters were only able to issue a hurricane warning 21 hours before Andrew’s destructive winds moved ashore.

DON'T MISS: How hot water fuels the world’s most powerful hurricanes

The U.S. National Hurricane Center's official forecast for Hurricane Juan on September 25, 2003. (NOAA/NHC)

Compare that to Hurricane Juan eleven years later. The NHC’s forecast ahead of that storm in September 2003 more or less pinpointed landfall three full days before the storm hit Nova Scotia. Forecasts have improved even more since then.

What does all this mean in practical terms? A storm’s arrival almost never takes communities by surprise anymore. The tremendous improvement in track forecasts several days in advance gives communities in harm’s way ample time to prepare for a storm and evacuate ahead of dangerous conditions.

Intensity forecasts are better as well

Intensity forecasting has gotten better over time as well. The factors that contribute to a storm’s track are much more concrete than the ingredients behind a storm’s intensity.

MUST SEE: How a mammoth hurricane rapidly intensifies in mere hours

A hurricane’s intensity is driven by the structure of the thunderstorms around the centre of the storm. These thunderstorms are fragile and very sensitive to unfavourable conditions. Slightly cooler waters, a little bit of dry air, or interaction with land can significantly disrupt a storm and force it to weaken.

On the other hand, we’ve seen an increase in the number of rapid intensification events in the past few years. Rapid intensification occurs when a storm’s maximum winds intensify very quickly in just a day or two. Forecasters have gotten better at recognizing environments capable of supporting rapid intensification, but sometimes it still catches experts off guard.

The U.S. National Hurricane Center's official intensity error trend between 1990 and 2022. (NOAA/NHC)

We’ve seen gradual improvement in storm intensity forecasts over the past couple of decades. The average error in a storm’s predicted strength three days out in the early 1990s was about 20 knots, or about 46 km/h. Weather models and forecaster knowledge have improved to cut that three-day error in half today.

Header image created using Getty imagery through Canva.