Why chickens might be the biggest legacy we leave on Earth

Before you throw away that chicken bone, you should know: It may wind up on our permanent record.

A study released by researchers in England last December showed that our lasting legacy here on Earth may be just that, as the sheer number of the world's most popular fowl stands to leave its mark on this slice of the geological record.

Think you know your birds? See if you can name all of Canada's provincial birds in this quiz.

At any given time, there are an estimated 23 billion chickens on Earth; about 10 times more than any other bird species. They've got us outnumbered, too -- that's about 3 chickens for every person on the planet. According to the study's authors, the world's domesticated chickens "is likely to be the largest standing population of a single bird species in Earth's history."

That's a big feat for one little bird, and as you might expect, humans played a role in their rise to the top of the pecking order.

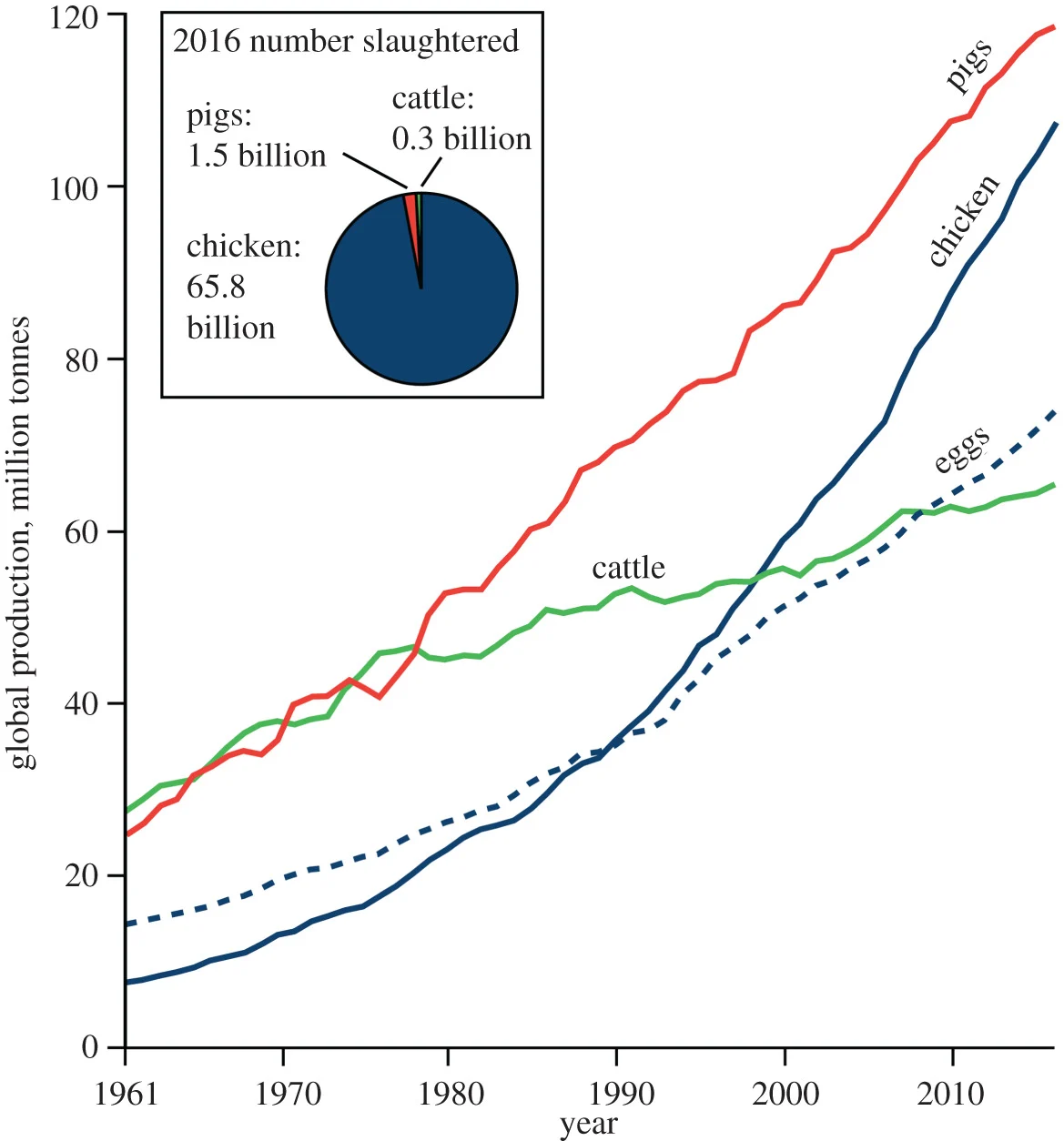

Above: Global consumption of domesticated chicken, pig and cattle from 1961 to 2016. Chicken is the most common meat consumed, with a standing population in 2016 of over 22.7 billion. The number of chickens slaughtered per year is an order of magnitude larger than that of pigs or cattle. Data compiled from UN Food and Agriculture Organization, FAOSTAT, at faostat.fao.org, accessed November 2018. Image courtesy The Royal Society.

For one thing, today's chickens are bigger -- a lot bigger -- than their counterparts of as recently as the mid-1900s. "Human-directed changes in breeding, diet and farming practices demonstrate at least a doubling in body size from the late medieval period to the present in domesticated chickens," says the study, "and an up to fivefold increase in body mass since the mid-twentieth century."

Above: Limb bones (femur, tibiotarsus, tarsometatarsus) of a modern broiler and a red jungle fowl. Image courtesy The Royal Society.

SEE ALSO: The world's most dangerous bird makes for a deadly pet

The study also found distinct changes in the genetic and chemical makeup of the birds. In fact, we've modified the modern broiler chicken so much that it's unable to survive without human involvement.

The study cites the rapid growth of leg and breast muscle -- something that's been specifically bred for since the 1950s -- leaves the animals' other organs unable to function properly. Changes to the birds' bodies have also left them prone to lameness and other movement issues. "This new broiler morphotype is shaped by, and unable to live without, intensive human intervention," conclude the researchers.

While bird bones don't typically fossilize very well, they do have numbers on their side. And how we dispose of these billions of bones plays a part, too.

Young broiler chickens at the poultry farm. Image courtesy Getty Images.

"Bird carcasses in the wild are scavenger- and decay-prone and so do not commonly fossilize. Chicken bones, by contrast, are often sold intact within products for human consumption, such as chicken wings, drumsticks and whole birds, and post-consumption the discarded bones form a common component of ordinary landfill sites as part of domestic garbage." When buried in landfills, organic matter -- such as chicken bones -- tends to be better preserved.

We've heard a lot lately about the lasting mark humans are leaving on the planet, from mountains with rivers of human waste to mountains infiltrated by microplastics. But it's a different mountain that may have archaeologists of the distant future raising an eyebrow.

Mountains of chicken bones.

Sources: The Royal Society | The New York Times | Science |