COVID-19 will slow the shift to renewable energy, but can’t stop it

A short-run contraction is likely, followed by a catch up period, with long-term momentum continuing

The renewable energy industry, which until recently was projected to enjoy rapid growth, has run into stiff headwinds as a result of three era-defining events: the COVID-19 pandemic, the resulting global financial contraction and a collapse in oil prices. These are interrelated, mutually reinforcing events.

It’s much too early to be able to assess how large their economic, environmental and policy impacts will be. But as someone who has worked on energy policy in academia, the industry, the federal government and Wall Street, I expect a significant short-run contraction followed by a catch-up period over the next few years that returns us to the same long-term path – perhaps even a better one.

Go HERE for our complete coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic

FALLING ENERGY DEMAND

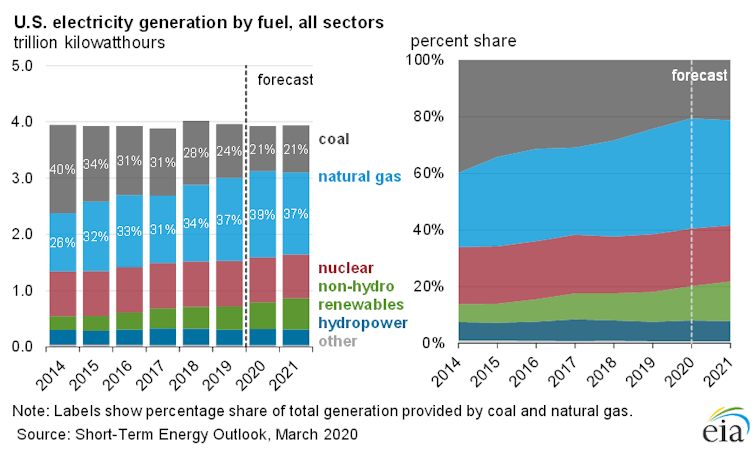

The most obvious result of these shocks is clear: Economic contractions reduce power demand, because every form of economic activity requires electricity, directly or indirectly. The 2008-9 recession reduced power demand in the United States by about 10 years’ worth of growth. Put another way, national utility sales did not exceed 2008 levels until 2018.

U.S. electricity use on March 27, 2020 was 3% lower than on March 27, 2019. That difference represents a loss of about three years of sales growth. Electricity use will trace the same path as total economic output as the crisis unfolds, but will drop much less in percentage terms. That’s because electricity use is a necessity, and essential services and households will continue to use power. Some, like health care, will use much more.

Industry revenues will also suffer, because most utilities are voluntarily halting shutoffs due to bill nonpayment and deferring planned or proposed rate increases.

Economy-driven demand reductions, which are likely worldwide, will hurt new renewable installations. Utilities will tighten their budgets and defer building new plants. Companies that make solar cells, wind turbines and other green energy technologies will shelve their growth plans and adopt austerity measures. For example, Morgan Stanley’s highly respected clean tech analysts project declines of 48%, 28% and 17% in U.S. solar photovoltaic installations in the second, third and fourth quarters of 2020, respectively.

WATCH BELOW: HOW WEATHER DATA IS BEING USED BY RESEARCHERS STUDYING COVID-19

CLEAN ENERGY HAS MOMENTUM

Countervailing factors will partly offset this decline, at least in wealthy countries. Many renewable plants are being installed for reasons other than demand growth, such as clean power targets in state laws and regulations, and are already under contract or construction.

Government policies and public pressure are also forcing utilities to retire coal-fired power plants. Since 2010, 102,000 megawatts of coal generating capacity have been retired – nearly one-third of the total U.S. coal fleet – and at least 17,000 megawatts more are expected to retire by 2025. Most of this will likely be replaced by wind, solar and hydropower.

Despite the current crisis, there is long-term pressure from many directions to add carbon-free energy. Fifty U.S. utilities have already committed to carbon reduction goals, including 21 companies that pledge to become carbon-free by 2050.

Voluntary green energy purchases by U.S. companies increased by almost 50% in the last year, to 9,300 megawatts – almost 1% of all U.S. power capacity. And residential customers are choosing to buy more renewable energy through options such as community solar programs.

DEFAULTING TO DIRTY FUELS

Since early 2019 crude oil prices have collapsed, declining almost 64%. As oil market guru Daniel Yergin recently observed, this drop is likely to be steep and prolonged:

“[I]t’s a problem of an oil price war in the middle of a constricting market when the walls are closing in. Normally demand would solve the problem in a way, because you would have lower prices that act like a tax cut and it would be a stimulus. But not in this case because of the freezing up of economic activity.”

Oil companies are bracing for a prolonged period of low prices.

This oil price collapse has also reduced U.S. natural gas prices by about one-third from year-ago levels. Like electricity and oil, natural gas use rises and falls with economic activity; it is somewhat less sensitive to economic trends than the highly reactive oil sector, and more sensitive than comparatively stable electricity use.

Ordinarily, cheaper natural gas – which is widely used for generating electricity – would stimulate electricity demand by reducing the price of power, thus increasing economic growth. But in this unusual era, the effects of lower oil and gas prices on renewables will be somewhat murky and complex, and will probably differ substantially by market and region.

For some new plants in places where policies do not effectively mandate renewable energy, continued or even new use of oil and gas generation will look cheaper. For example, replacing dirty diesel generation with solar power plus some form of energy storage will not look nearly as attractive now as it did a year ago.

This is especially worrisome in emerging nations, where the overwhelming imperative is to expand electricity supply as cheaply as possible. These economies are always short on capital and highly sensitive to energy costs. If they opt for cheap fossil fuels instead of renewables, it will be bad for air quality and climate policy.

The fact that central banks are promoting ultra-low or even negative interest rates to respond to the economic crisis could mitigate this risk by making renewables, which have high capital costs, cheaper to install. The key is avoiding a wholesale shift to new fossil fuel generation.

PARTS SHORTAGES

The most significant near-term impacts on renewable plants that are already contracted or under construction may be felt through supply chains. Renewable industry executives are anticipating delivery and construction slowdowns, either because nations shutter industries to slow the spread of coronavirus or because workers start getting sick.

Many parts for large-scale renewable projects come entirely or partially from China, other parts of Asia or the United States. These are specialized supply chains with few ready substitutes.

The COVID-19 outbreak has already slowed Chinese production of solar panels and materials, delaying projects in countries including India and Australia. Manufacturing disruptions in China could contribute to a significant one- or two-year dip in renewable additions.

All in all, I expect that a slowdown in renewable energy growth will be one of many deeply tragic effects of the virus-plus-contraction double whammy. Impacts in emerging markets, where a new fossil-fueled plant locks in decades of new carbon dioxide emissions, are especially concerning.

But these effects will not be uniformly negative, and nothing about this crisis will change the long-term trend toward carbon-free energy. Once the global economy bounces back, perhaps this episode will convince world leaders to accelerate climate policy efforts, before the next climate-induced disease vector or weather event triggers yet another global economic shock.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for our newsletter.]![]()

Peter Fox-Penner, Director, Institute for Sustainable Energy, and Professor of Practice, Questrom School of Business, Boston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.