Is hacking the atmosphere a 'cool' idea to offset global warming?

A compelling idea to counter the warming Earth has been brought forward in the scientific community. Is it a doable solution? Or, does it have too much risk involved? See what some experts have to say

With governments and scientists trying to find tangible solutions to cool our planet and limit warming to a 1.5 C to 2 C temperature rise during this century, a new idea has been pitched to stop that from occurring, but it comes with calculated risks, experts say.

Details of a new geoengineering scheme, published in Science Advances, outlines the theoretical idea that the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere can be limited or reduced by seeding the layer just below it –– at the top of the troposphere.

RELATED: Answer to high ocean acidity may lie in carbon transfer from wetlands

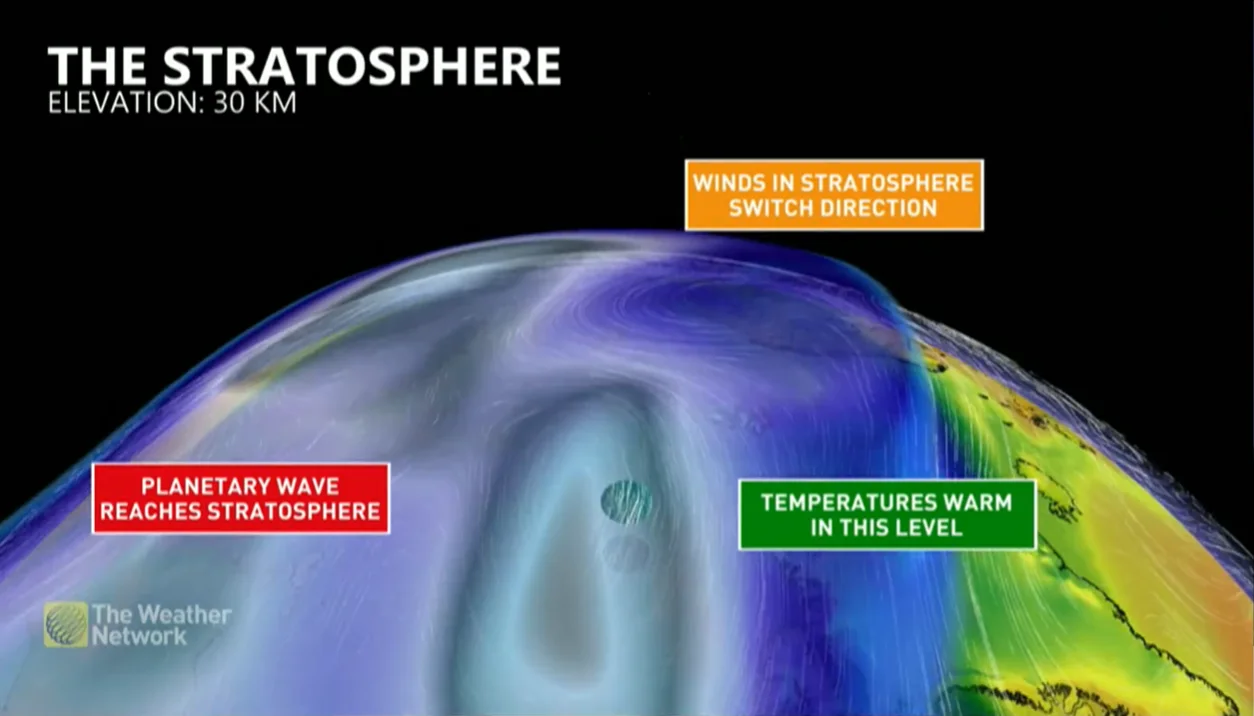

The concept would involve focusing on rising, moist air and seeding it with cloud-forming particles just before it crosses into the stratosphere, according to the study.

If the plan was to be enacted, how much drying would be required?

Well, according to Shuka Schwarz, the study's lead author and a research physicist at the Chemical Sciences Lab of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the procedure may only require as little as two kilograms of material each week.

“That’s an amount of material that helps open the mind to imagine a whole bunch of possibilities,” Schwarz told Science.org.

Intentional stratospheric dehydration

The study cited a 2010 examination from Sciences Advances, which stated a rise in the amount of water in the stratosphere in the 1990s could have enhanced global warming by as much as 30 per cent during that decade.

When talking about greenhouse gases, including methane and carbon dioxide, we also have to mention water vapour. It is a significant greenhouse gas, actually, which can hang around for years in the stratosphere. The water vapour then absorbs heat from the surface and filters it back down, resulting in further warming.

(acilo. E+./Getty Images)

The new plan is referred to as intentional stratospheric dehydration, which, theoretically, has a chance of cooling the climate in modest amounts, the study noted. But, it would only offset approximately 1.4 per cent of the warming that has led to a spike in CO2 levels over hundreds of years.

As part of its scheme, the team involved in the study conducted a simulation that involved inserting bismuth triiodide, a non-toxic compound previously utilized in lab studies of ice nucleation, into the one per cent areas most suitable for water harvesting.

In one potential scenario, as mentioned previously, as little as two kilograms of seeds 10 nanometers in diameter every week would be sufficient to convert the moist air parcels into clouds, they found. Because of how little it is, the authors believe the amount could be sprayed by balloons or drones, with no airplane needed.

(Getty Images/Godruma/653320058-170667a)

WATCH: What is geoengineering and how can it defend against climate change?

What are the drawbacks? The Weather Network chimes in

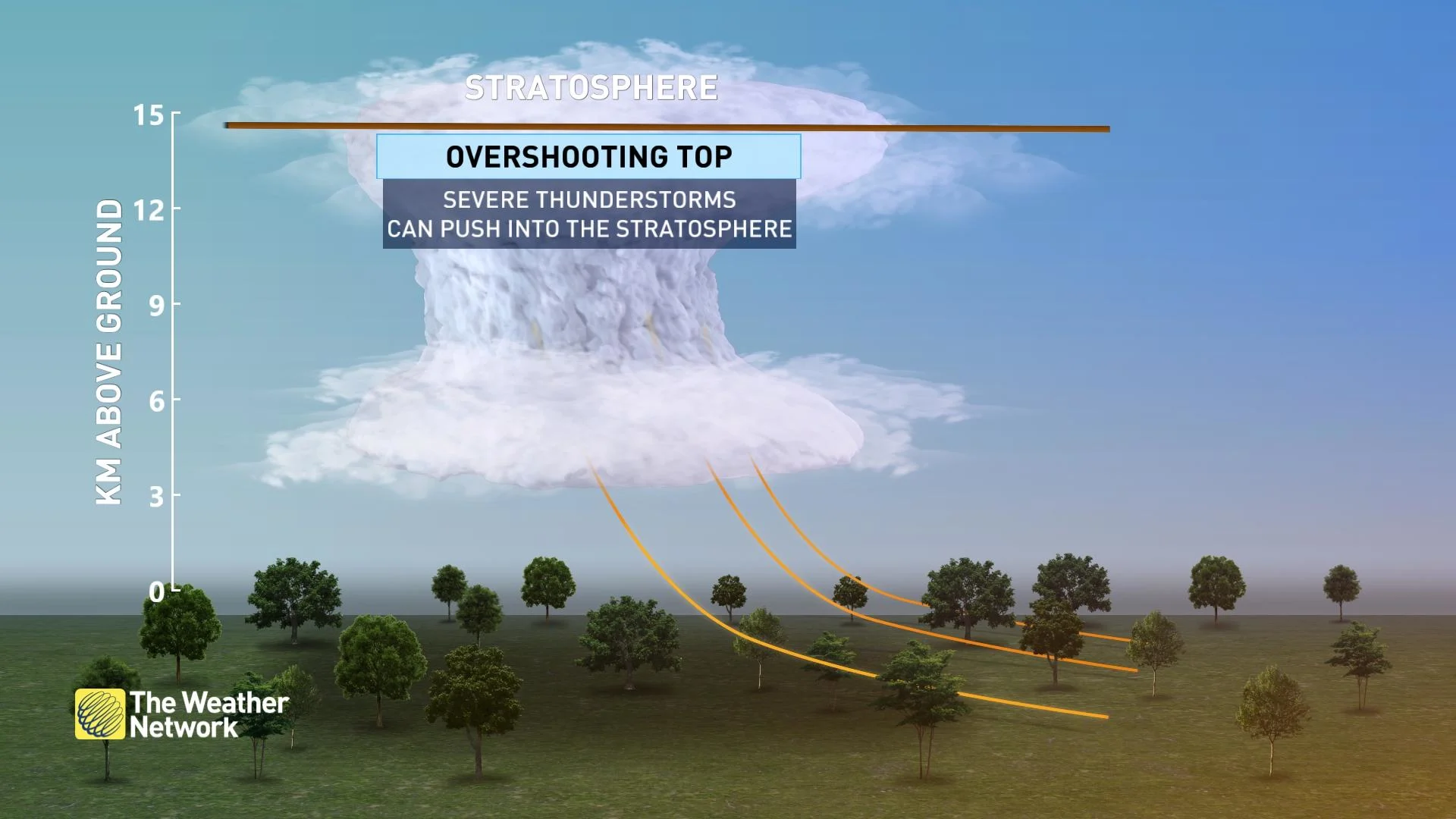

When looking at the proposal, the main technical drawback is how do we get dryer air in the stratosphere? There are very few conduits that can take a parcel of air 10 kilometres above the surface of the Earth.

The highest thunderstorm cloud tops in Canada seldom reach 11 or 12 kilometres above the surface of the Earth, barely reaching the tropopause and only occasionally getting to the stratosphere. That represents a stumbling block for elevating the parcel of air.

The study centred on the western equatorial Pacific Ocean, in an area approximately the size of Australia, as the most vital portal for getting dryer air into the atmosphere, if it can be done effectively.

But, how realistic is it?

Scott Sutherland, science writer and meteorologist at The Weather Network, said artificially introducing particles into the top of the troposphere could effectively reduce the amount of water vapour intruding into the stratosphere.

However, there are problems with this idea, as with all methods of geoengineering, he added.

The biggest issue it faces would be its longevity. Such a program would need to run indefinitely in order to be effective, Sutherland said, "regardless of the changing political climate here on the ground."

(Getty Images/Edin/17652584-170667a)

"Any offset warming would immediately return, possibly worse than before, if the program was discontinued," said Sutherland.

Methods such as this, which aim to offset warming from emissions, ultimately become "distractions from what we truly need," Sutherland said. And, what the world needs is to reduce and eventually end the burning of fossil fuels, "the sooner the better."

"As with pretty much every form of geoengineering that's been proposed so far, stratospheric dehydration is essentially just a thought experiment at this time," said Sutherland.

What do other experts have to say?

The idea that has been put forth on the table as a possible tool to combat global warming has been met with intrigue but caution, as well, about the potential risks associated with such a scheme.

Daniel Cziczo, an atmospheric chemist at Purdue University, told Science.org the idea is interesting, but it could have a downfall.

(Getty Images/Apomares/157286081-170667a)

If the seeds are unable to generate clouds in the proper place and extend to other areas, they could inadvertently cause the wrong type of clouds to speed up, he said. That includes thin, wispy, cirrus clouds, which don't reflect much sunlight, and instead, tend to soak up infrared heat from the surface.

“You’re basically exploring a technique that could have a warming effect and not a cooling effect," said Cziczo.

Atmospheric scientist Mark Schoeberl, who works at the Science and Technology Corporation, also echoed the call for additional study into the proposition at hand. “You want to avoid unintended consequences and make a clear-eyed assessment of implementation cost,” he told Science.org.

One of the pitfalls of intentional stratospheric dehydration would be its limited effectiveness, Schoeberl said, since most water hits the stratosphere during the Asian monsoon seasons. As well, there's uncertainty in how much of a reduction in stratospheric water would ultimately cool the surface.

WATCH: CO2 "cages" could be developed to trap carbon in the ocean

Are governments open to geoengineering?

The thought of geoengineering is far from a new idea, with ongoing discussions around its potential effectiveness and side-effects for many years. One such scheme has been to block out the sun's rays, drawing mostly negative criticism from the scientific community.

However, it appears that some governments are at least researching geoengineering to determine the validity of the proposals, though.

(NASA/Greg Nelson)

In June 2023, the U.S. White House released a federally mandated report on solar engineering, presenting information on what a research program would look like on it and why it could be helpful. At this stage, the U.S. government hasn't put any plan into motion to launch a comprehensive research program into solar radiation modification.

Overseas, the European Union (EU) has asked for global talks on the inherent dangers and governance of geoengineering, reported by Reuters in 2023. It said meddlesome action to change the climate comes with "unacceptable" risks.

(Getty Images/Henrik5000/175205370-170667a)

But, at least one European country wants further research into the matter. In February, Switzerland made the pitch for the United Nations to collect information about the current research into solar geoengineering, to determine the risks, benefits and uncertainties on it. As well, it wants the UN to establish an advisory panel that could recommend future options for the approach to reduce global heating.

But, at the end of the day, the ideas for modifying the planet's weather are still hypothetical. There are no global-scale solar geoengineering projects currently in operation, nor are there any in development, says Sutherland.

WATCH: Ocean aerosol research explores impacts on climate

Thumbnail courtesy of Getty Images/Elen11/1138412391-170667a.

With files from Scott Sutherland, a science writer and meteorologist at The Weather Network, and Tyler Hamilton, a meteorologist at The Weather Network.

Follow Nathan Howes on the X platform, formerly known as Twitter.