How industrial waste is keeping these Ottawa-area buildings warm

Residents of a new development in Ottawa-Gatineau are using industrial waste to keep their homes warm — specifically, waste heat from a local paper plant. Heat is being thrown away all around us.

SEE ALSO: Here’s how food waste can generate clean energy

But it doesn't have to be — it can be captured to heat buildings in a more efficient and climate friendly way.

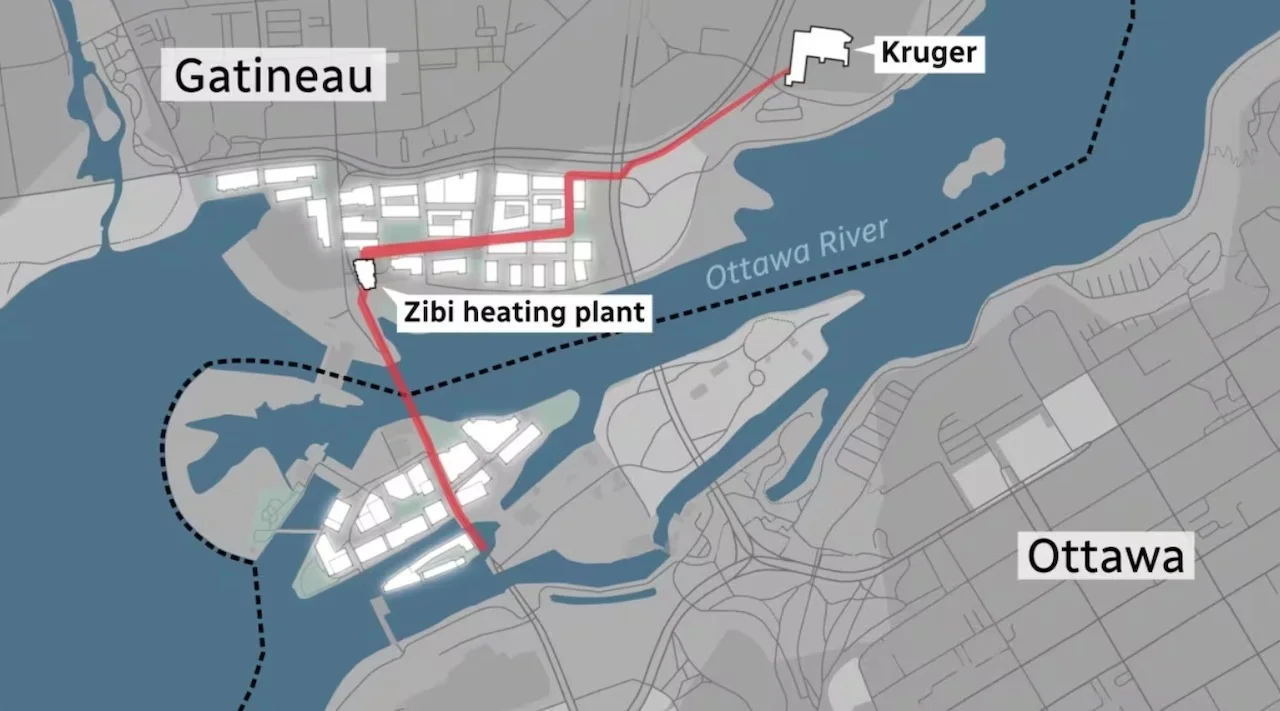

That's exactly what's happening at the Zibi development along the Ottawa River in Ottawa-Gatineau. So far, 615,000 square feet of residential and office space on either side of the river are being heated with waste heat from the nearby Kruger Products Plant in Gatineau, Que., and more buildings are under construction.

What it's like to use waste heat to keep warm

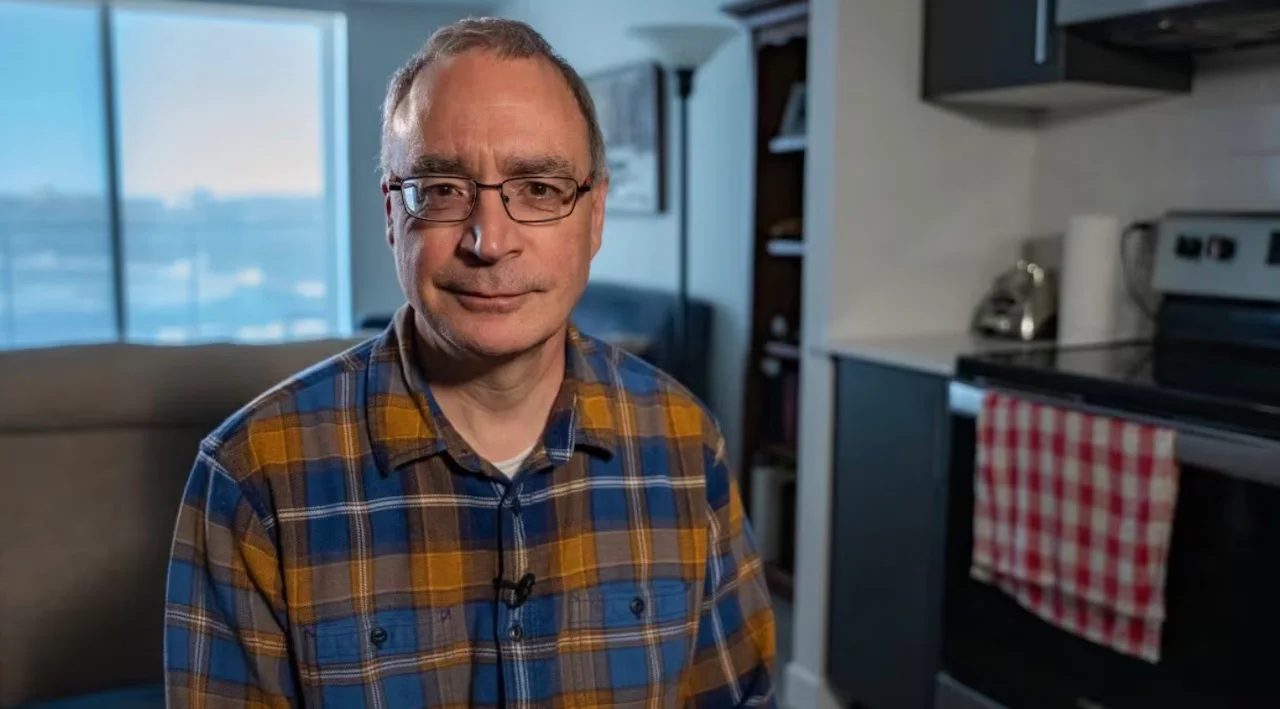

It's something Guy Faubert, who lives on the ninth floor of a 15-storey building on the Gatineau side of Zibi, is excited about. In fact, it's one of the reasons Faubert, an engineer by training who has worked in the EV sector, chose to move into the building two years ago.

"Absolutely, it was a big part of my decision," he said. "Anything that you can do to reduce your environmental impact is something which is of interest to me."

Guy Faubert lives in an apartment in Gatineau, Que., heated by waste heat from the nearby Kruger Products paper plant. He says the comfort is 'exceptional' and the environmentally friendly heating system was one reason he chose to live in the development. (Mathieu Theriault/CBC)

His tower is part of a district heating system run by Zibi Community Utility and Hydro Ottawa, a network that allows many buildings to share a single heating and cooling system instead of having their own individual boilers and chillers.

A network of water pipes distributes industrial waste heat for heat and hot water; it also offers cooling in the summer using water from the Ottawa River.

Air conditioning isn't too common in apartments in the region. Faubert said the cooling system is "absolutely essential" as summers get warmer due to climate change.

Faubert controls the temperature in his apartment with a thermostat, like anyone else.

"I find the comfort inside my unit to be exceptional," he said. "The system is very responsive and very effective and very quiet."

His energy bills, he said, are similar to what he paid with a more traditional heating system in his previous apartment in Ottawa. "So I'm very happy about that."

The heat's journey

The Kruger Products plant makes giant rolls of tissue paper from recycled paper and other fibre that get turned into paper towels and tissues at other plants.

Stephane Lamoureux, vice-president of operations and special projects at Kruger, said the plant burns natural gas, both to heat water from the Ottawa River to make the paper, and then to dry the paper.

Steam rises from the settling tank at Kruger Products. The heat from this wastewater is what gets transferred to the Zibi buildings. (CBC)

The waste heat produced in the process is visible as plumes of steam pouring from the plant's smokestack on cold winter days. It's something that caught the eye of Scott Demark, a partner with developer Theia Partners.

The company was building a new mixed-use development called Zibi "next door, practically," and he recalled thinking, "'How can we harness that and bring it here?' It's silly to be dissipating that to the atmosphere and turning around and burning gas or something to make heat."

When Zibi approached Kruger about using its waste heat, Lamoureux said the idea was "perfectly in line" with the company's long-term strategy to reuse energy.

Engineers from Kruger and Zibi worked together, and decided to take heat from a later part of the process. After paper-making, water that is 25 to 30 C cools in a huge, steaming "settling tank" before being returned to the Ottawa River.

A map shows how heat travels from the Kruger plant to buildings in the Zibi development in Ottawa and Gatineau, Que. The white buildings include both completed and planned construction, which is expected to total four million square feet. (CBC)

Technicians installed heat exchangers on the Kruger property to transfer some of that heat to the water in the interprovincial district heating network. "We don't take their water," Demark explained "just their heat." The Kruger water is discharged, cooler than before, into the river.

Meanwhile, the heat continues on to Zibi Community Utility's central heating plant, just down the street.

At the plant, the heat is processed as needed, and directed to different parts of the system. In winter, the warm water goes to the Quebec Zibi buildings, which extract the heat with their own water-source heat pumps.

Because electricity is more expensive in Ontario and more greenhouse gas emissions are produced from the province's gas plants, Zibi pre-heats the water destined for its Ottawa buildings to 42 C in Quebec. Then it sends the water to Ontario via pipes mounted under the Booth Street bridge. Fans blow the heat into individual units as needed.

In the summer, the system largely bypasses Kruger, exchanging heat directly with the cool Ottawa River to provide air conditioning.

Scott Demark, president of Zibi Community Utility, says the system is capable of delivering enough heat for four million square feet of indoor space. (CBC)

The system was built with funding from the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, Natural Resources Canada, Hydro Quebec and Hydro Ottawa, and went online in 2021. But construction continues, and it's expected to eventually quintuple its current size to heat a total of four million square feet.

Other options, from nuclear, steel, waste and sewage

Capturing heat from industrial processes for space and water heating isn't common in North America. Zibi says it's the first in North America to use post-industrial waste recovery in a master-planned community.

But other parts of the world have been using industrial heat this way for some time. Sweden is known for powering and heating its cities with its waste-to-energy plants, which dispose of the country's garbage while generating both electricity and district heating.

In Dunkirk, France, an ArcelorMittal steel plant has been supplying heat to a hospital, schools, commercial buildings, and public and private housing since 1985. In Haiyang, China, a nuclear plant has been providing district heating to the entire city since 2020, and a long-distance heating pipeline is now being built to reach another million residents farther away.

The black pipes in the foreground carry water heated in Quebec under the Booth Street bridge to the Zibi buildings in Ottawa. (CBC)

Interest is also growing in Canada. Last year, the Quebec government announced $162 million for projects that recover waste heat for other uses. It noted that industrial facilities, wastewater treatment plants and other heat producers dump 300 petajoules of heat energy a year – almost the same amount of heat needed by large buildings and greenhouses across Quebec each year. It said each petajoule could alternatively heat 10,000 homes.

The heat in wastewater – from industry, laundry, showers and dishwashers – has been used in a district heating system in Vancouver since 2010 that is now being expanded. A new system under construction by Toronto-based Noventa Energy Partners at Toronto Western Hospital is expected to be the largest raw wastewater energy project in the world. The first phase is scheduled to be completed in June.

Stephen Condie, chief technology officer at Noventa, said the project is expected to save the hospital $685,000 annually in energy bills. It's also expected to cut about 8,400 metric tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions a year, equivalent to removing 1,811 cars from the road.

WATCH: New study aims to help cities better manage landfill emissions

Michael Wiggin is a director of the Boltzmann Institute, a Canadian non-profit that does research on and advocates for district energy. He thinks these projects are just the beginning.

He recently spoke to the nuclear industry about the possibility of recovering heat from Canada's nuclear plants. For example, he estimates that waste heat from the Pickering, Ont., nuclear plant could heat all of Toronto.

Similarly, a study from the institute concluded that blast furnaces at the steel mills in Hamilton could heat most of that city's downtown core. Other sources of waste heat could include refineries in Regina, other kinds of power plants, or even smaller facilities such as data centres.

"I think now the interest is growing, the awareness of the possibilities is growing," Wiggin said. "Every community has different opportunities."

Thumbnail courtesy of CBC.

The story was originally written by Emily Chung and published for CBC News.