Giant iceberg A-68a shatters after collision with South Georgia Island shelf

Scientists are concerned this massive iceberg may still disrupt an important wildlife sanctuary.

Update 2 (December 22, 2020): Satellite imagery has captured iceberg A-68a breaking apart into at least four large pieces, after an apparent collision with the shelf surrounding South Georgia Island.

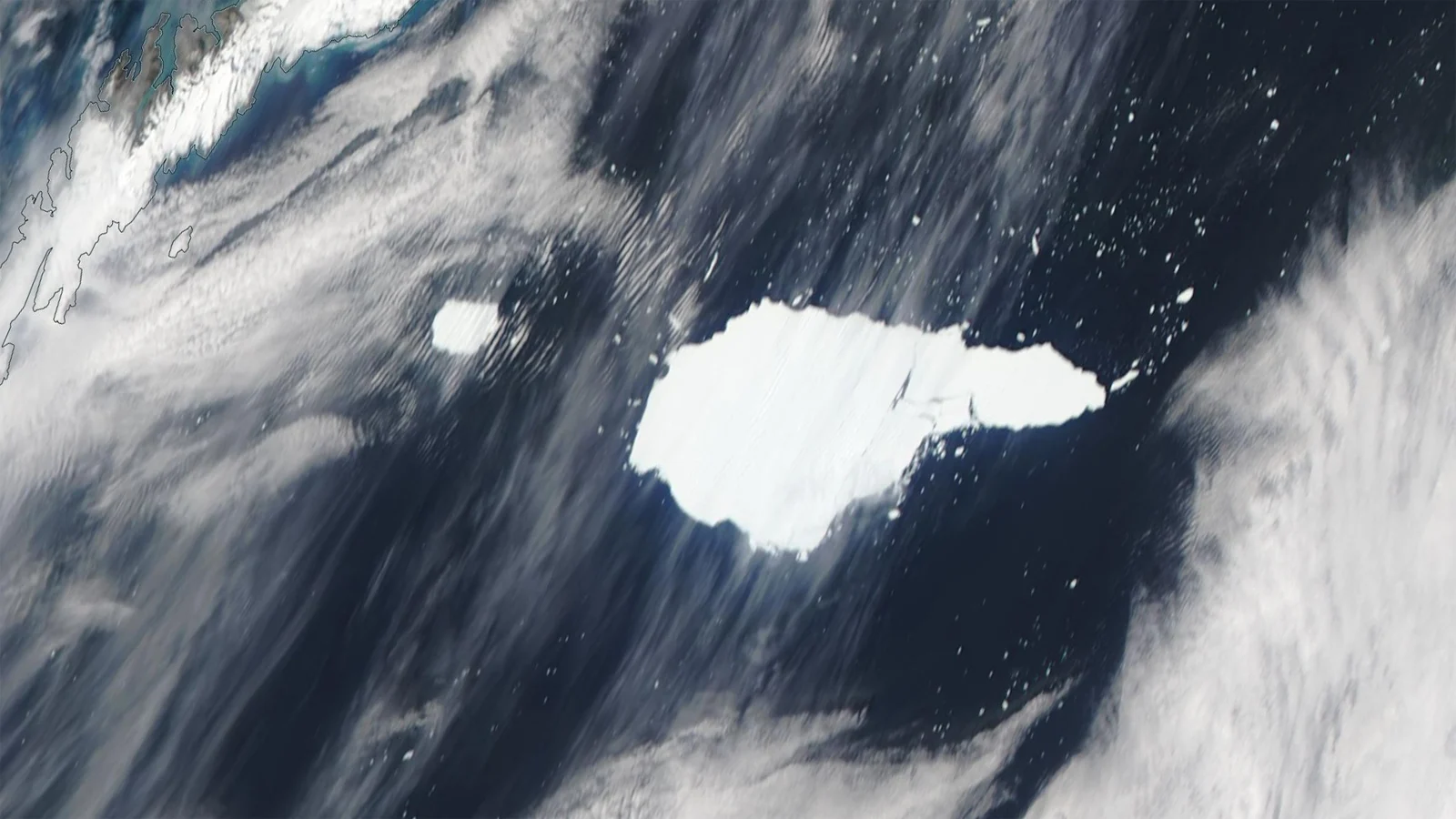

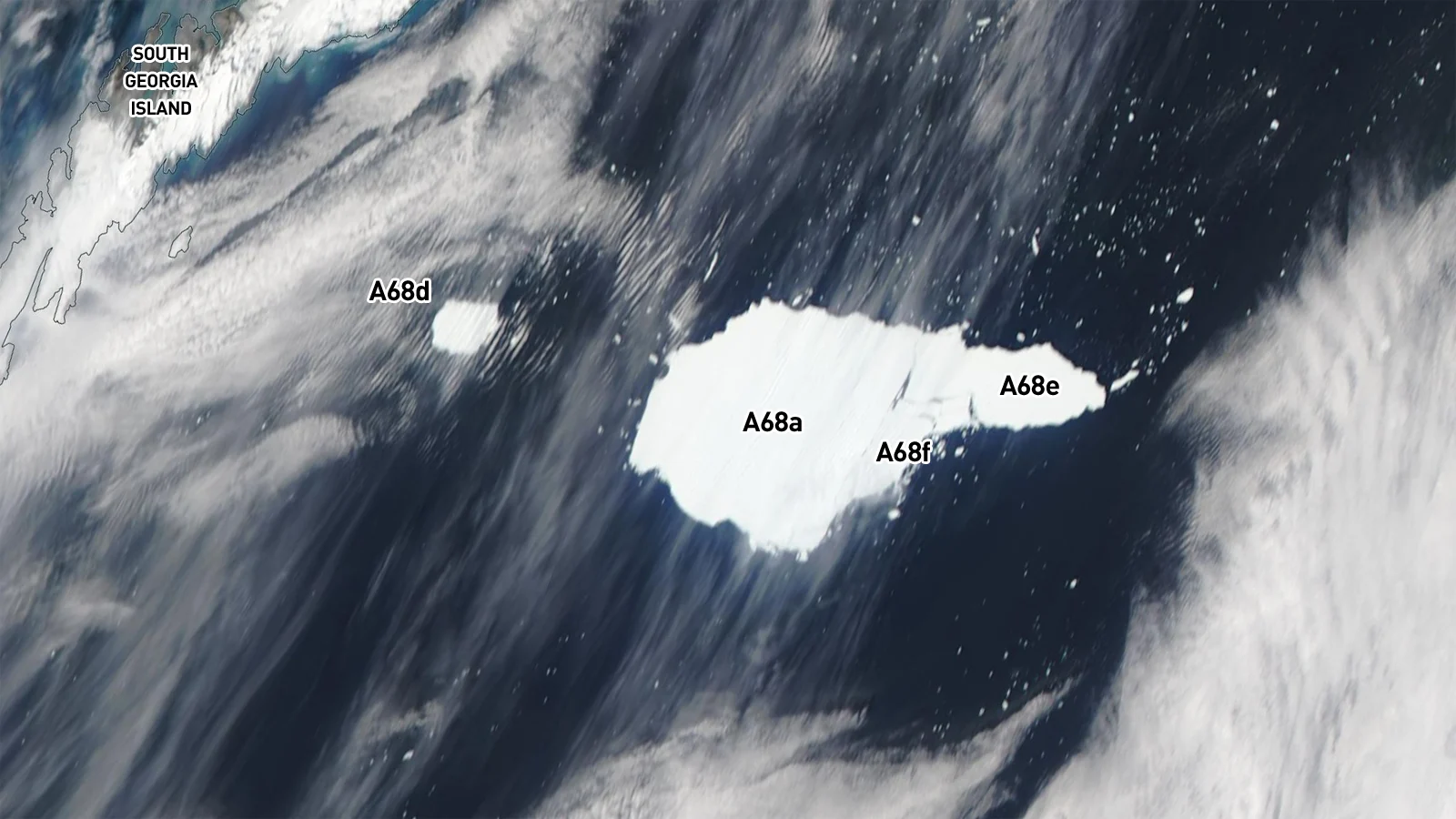

This image captured by the MODIS instrument on NASA's polar orbiting Aqua satellite shows iceberg A68, now fractured into four main parts. Credit: NASA Worldview/Scott Sutherland

The first piece to break away that was large enough to earn its own name was A68d, which appeared on December 17. From imagery taken at the time, the trailing end of the iceberg may have impacted on part of the island shelf, causing it to calve off. On December 22, ice analysts Michael Lowe and Chris Readinger with the US National Ice Center discovered that the leading edge of the main body of A68a had shattered into at least two more large chunks. These are now named A68e and A68f.

Ocean currents are currently carrying the bulk of A68 southward, away from South Georgia Island. However, with potential for those same currents to draw A68 back towards the island in the days ahead, it is still unclear if the island's wildlife population has been spared.

The original story continues below...

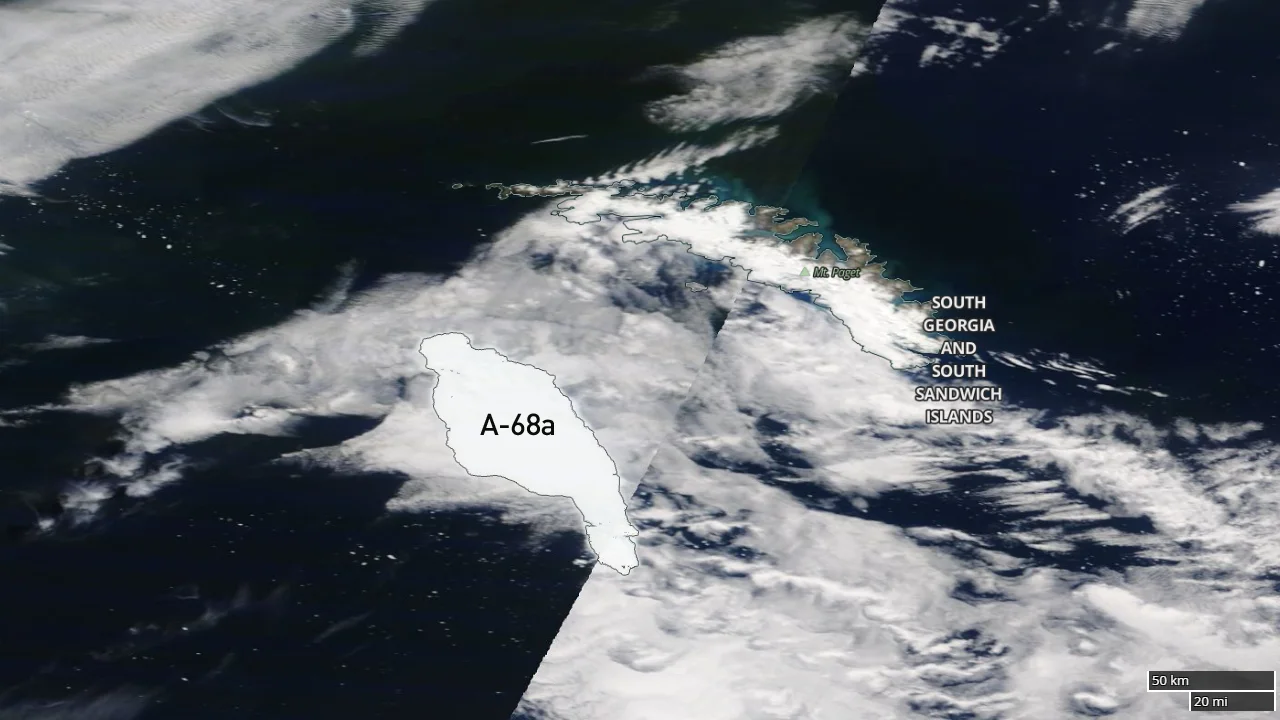

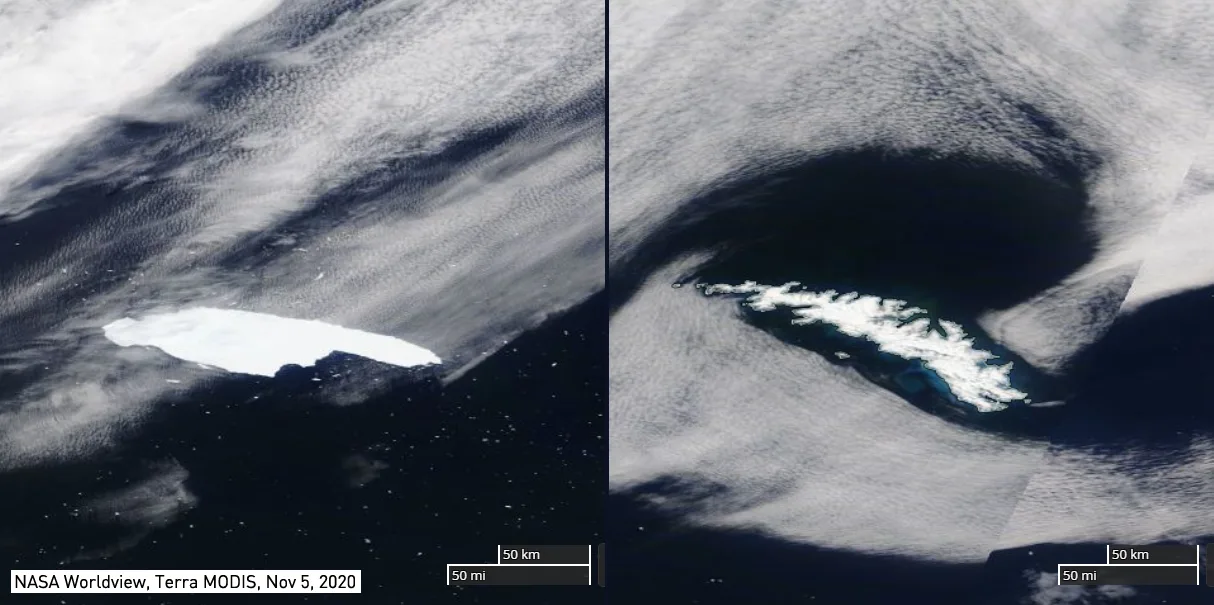

Update 1 (December 14, 2020): Iceberg A-68a is within 100 kilometres of South Georgia Island. After drifting 300 kilometres farther on the ocean currents since early November, the immense iceberg is now right up against the southwestern edge of the shelf that surrounds the island.

)Imagery of A-68a and South Georgia Island, on December 14, 2020, taken by NASA's polar-orbiting Terra satellite. Credit: NASA Worldview

It is still unclear if the iceberg has grounded itself on the island shelf. Satellite imagery in the days to come will reveal whether it is stuck, or if the ocean currents can carry it away and around the island.

Iceberg A-68a is causing new concerns. On its present course, it is approaching the island of South Georgia, where it may run aground, potentially damaging a critical wildlife refuge.

In July of 2017, iceberg A-68 made headlines as it broke off Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf. It became the most massive intact iceberg in the world at the time and one of the largest ever recorded. It also raised concerns about the future of the ice shelf. Similar large calving events heralded the collapse of the Larsen A Ice Shelf in 1995 and the Larsen B Ice Shelf in 2002.

While scientists continue monitoring Larsen C, they have also kept track of A-68's progress. Over the past three years, it first drifted out into the Weddell Sea, and as of the third anniversary of its birth, it was spotted moving out into the open waters of the Southern Ocean. Even now, although it has lost two sizable chunks big enough to earn their own names — A-68b and A-68c — the parent body is still massive. A-68a is around 150 km long, 45 km across at its widest point, and tips the scales in the hundreds of billions of tonnes.

"A68a is spectacular," said Dr. Andrew Fleming, remote sensing manager for the British Antarctic Survey, according to BBC News. "The idea that it is still in one large piece is actually remarkable, particularly given the huge fractures you see running through it in the radar imagery. I'd fully expected it to have broken apart by now."

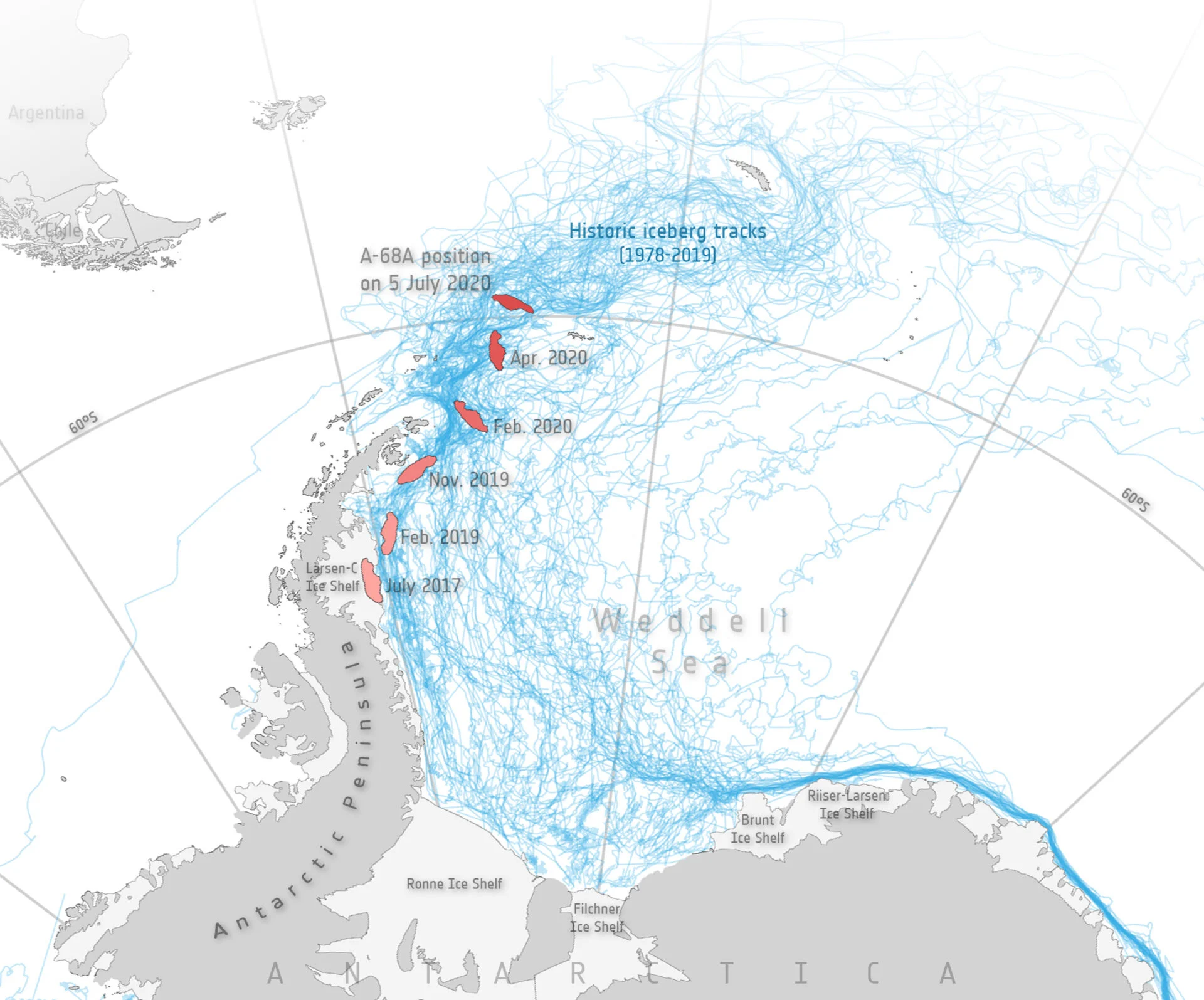

The track of iceberg A-68 up until July 5, 2020. Credit: European Space Agency

The latest imagery of A-68, captured by NASA and ESA satellites, has revealed a potential new situation.

A-68a is trapped in 'iceberg alley', an ocean current that sweeps these massive chunks of ice farther out to sea, but not before they pass by several islands in that region. As of November 5, 2020, satellite imagery shows A-68a less than 400 kilometres from the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia, and the current is carrying it directly towards the island.

Watch below: Satellites track the movement of A-68a as it closes with South Georgia

If the iceberg were to run aground in the shallow waters surrounding the island, it would likely disrupt the local ecosystem. Seals, penguins, and several sea bird species use the island of South Georgia for mating and raising their young.

"A close-in iceberg has massive implications for where land-based predators might be able to forage," Dr. Geraint Tarling, from the British Antarctic Survey, told BBC News.

"When you're talking about penguins and seals during the period that's really crucial to them — during pup- and chick-rearing — the actual distance they have to travel to find food (fish and krill) really matters," Tarling explained. "If they have to do a big detour, it means they're not going to get back to their young in time to prevent them starving to death in the interim."

"Ecosystems can and will bounce back, of course, but there's a danger here that if this iceberg gets stuck, it could be there for 10 years," Tarling added. "And that would make a very big difference, not just to the ecosystem of South Georgia but its economy as well."

Part of the concern about A-68a is its size in comparison to the island.

A size comparison between A-68a, as of November 5, 2020, and South Georgia Island. Credit: NASA Worldview

A-68a is moving along in iceberg alley at a rate of between 5-20 kilometres per day. With South Georgia surrounded by a shelf that extends about 100 km away from its shorelines, the iceberg is quickly closing in on the point where it could become grounded.

There is some hope for avoiding the disruption to this important ecosystem, though. At the same time as A-68a closes in on South Georgia, it is rotating in the flow of the current. Depending on its orientation in the flow when it reaches the island shelf, it may merely deflect off and continue on its way.

"If it spins around South Georgia and heads on northwards, it should start breaking up," Fleming told the BBC. "It will very quickly get into warmer waters, and wave action especially will start killing it off."