CO² gets absorbed into the ocean, but what’s coming out?

Atmospheric Scientist Dr. Rachel Chang is studying how aerosols and gases coming out of the ocean change what happens to particles in the atmosphere, which has implications on global warming.

What do waves kicking up sea spray as they crash in from the ocean have to do with climate change?

It's complicated.

But that hasn't stopped Dalhousie University atmospheric scientist Dr. Rachel Chang in her pursuit of learning about how aerosols and gases coming out of the ocean condense on existing particles in the air and actually change what happens to those particles in the atmosphere.

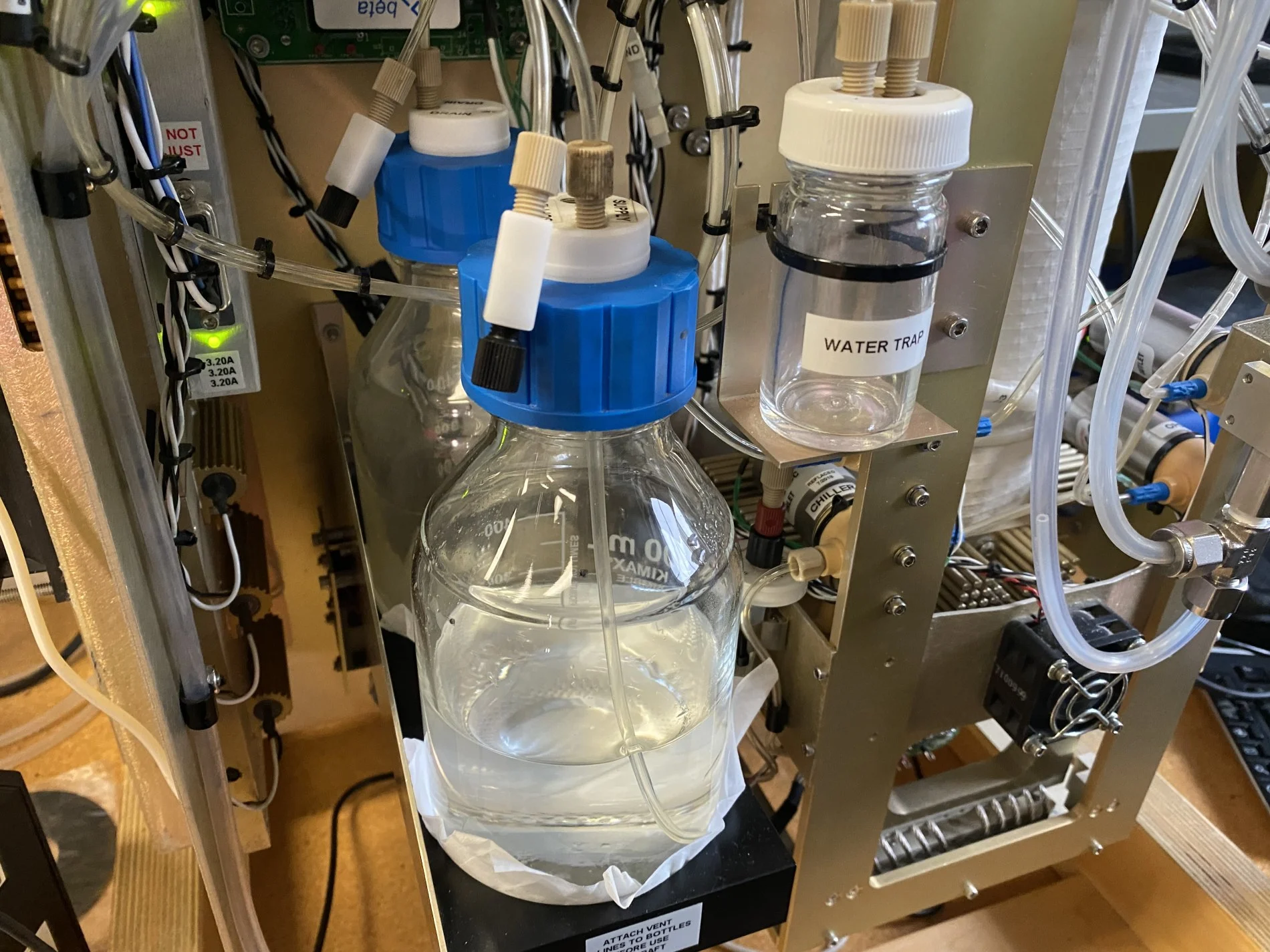

Water sample at Dr. Rachel Chang’s laboratory at Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S. (Nathan Coleman)

“Particles can directly reflect or scatter sunlight coming in from outer space,” Chang told The Weather Network. “All cloud droplets form on existing particles and those clouds affect radiation by reflecting sunlight back into space and reducing the amount of sunlight that reaches the surface.”

This has implications on global warming.

While the amount of carbon dioxide getting absorbed by the ocean attracts a lot of attention, Chang is more focused on how it impacts the biological activity in the ocean and what ends up coming out of the ocean as a result.

See also: Why scientists are studying the huge amounts of soot in deep sea trenches

"Part of the way that CO2 is taken into the ocean is through photosynthesis by the phytoplankton. So I'm interested in how the biology is affected by this increased CO2 but also, presumably, the biology is more productive when it's when there's more CO2 in the atmosphere,” Chang explained.

“The gases that are in the atmosphere that are emitted from the ocean — from the biology or from other sources — can react in the atmosphere to then condense to help grow the existing particles larger, and then that will make them more likely to turn into clouds. Therefore [it’s] more likely the clouds will also be brighter because of those gases," said Chang.

Dr. Chang studies data gathered one to two months at a time in the Arctic and North Atlantic Oceans. (Nathan Coleman)

"One of the reasons why the Earth has not warmed as much or as quickly as some initial models had suggested is because we've been emitting a lot of sulfur dioxide, particles into the atmosphere and it's actually brightened our clouds and increased our albedo and increased reflectivity," said Chang. Sulfur dioxide, of course, presents other issues as it’s toxic and can impact human, animal, and plant health.

The scope of what Chang hopes to study in the atmosphere requires long term measurement and will be a costly task. She now studies data gathered one to two months at a time in the Arctic and North Atlantic Oceans.

Along with three partner universities, Dalhousie has applied for $155 million from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund for a program that would study the ocean's essential role in climate.

Thumbnail image: Unsplash/Axel Antas-Bergkvist